Policy experimentation

A short introduction to policy experimentation

Overcoming the multiple challenges we face requires new policy ideas. But how do we know if our ideas actually work? At IGL, we help policymakers become more experimental to find effective evidence-based solutions.

What is an experiment? It’s a test – a structured way to find out if a policy or programme actually delivers the expected results. Policy experiments are used to generate information that supports decision-making. So an experiment is more than simply “trying something new”, it requires setting up a system that lets policymakers learn from their actions.

Why is it important? Experiments help explore new ideas and generate robust evidence. This helps policymakers figure out which ideas are worth pursuing, how to tweak a programme for better results, or when to pull the plug on something that’s not working.

How much can we learn from an experiment? Typically, a single experiment cannot provide all the relevant answers. It should be part of a broader experimental approach to policymaking, where complex challenges are broken down into smaller, more manageable questions. This approach creates a culture of continuous learning and improvement, helping to navigate and resolve uncertainty about the nature of the problem, the solutions that could be implemented and which are most effective.

How do experiments work? Experiments can serve two main purposes: aiding exploration and discovery (understanding how things work in the real world to establish rationale and inform design), or evaluating the impact of a programme (figuring out what works best). Ideally, experiments should start on a small scale to determine if they’re worth rolling out more broadly. By starting small, experiments can also help de-risk the process of exploring new policy ideas and changes. Various methods can be used to learn from experiments, including Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs), ethnographic research, and human-centred design.

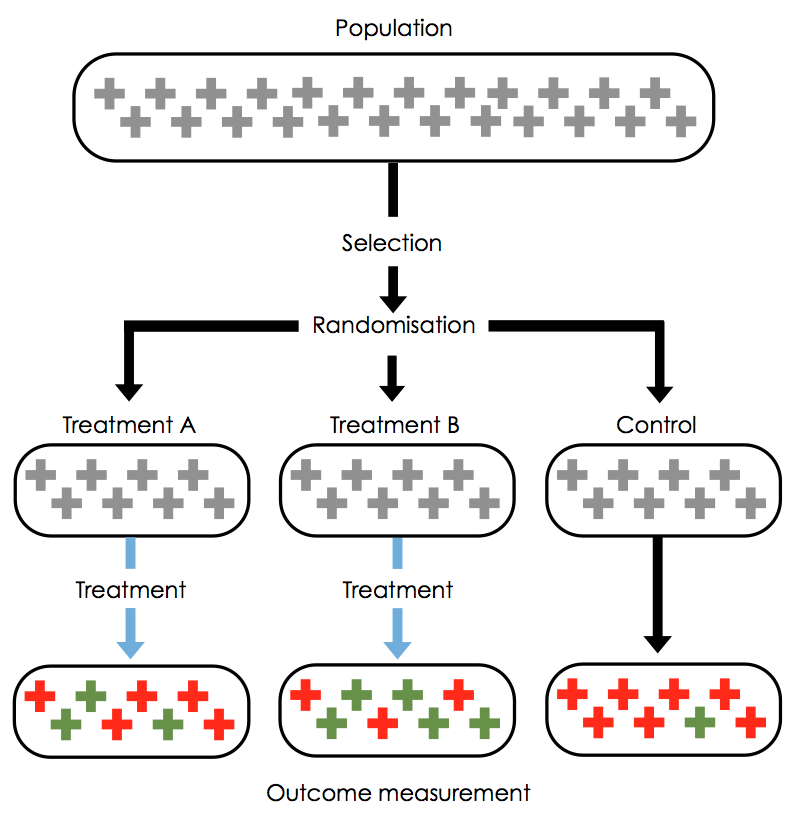

What is a Randomised Controlled Trial, or RCT? The central idea of RCTs is to allocate whatever is being tested by lottery. Specifically, participants are randomly placed across different groups, and the impact of the intervention(s) is estimated by comparing behaviours and outcomes across the two groups. The lottery used to assign participants to each group addresses potential selection biases. As a result, different groups are in principle comparable and any differences between the groups are the result of the intervention (as long as the sample size is sufficiently large to minimise the impact of noise). Therefore, RCTs can provide an accurate estimate of the causal impact of a programme.

Why are RCTs valuable? RCTs have the potential to provide the most reliable estimate of the causal impact of a programme or a change in its design, as they address a common pitfall of public policy evaluations. Many evaluations only give a good answer to the question “How well did the programme participants perform before and after the intervention?”, and fail to provide a compelling answer to the more important question: “What additional value did the programme generate?” Or in other words, is the improved performance of firms receiving the intervention the result of the programme itself, or does it reflect some unobserved characteristics of the firms that chose (or were selected) to participate in the programme? Answering this question requires good knowledge of how participants would have performed in absence of the programme, which is difficult to know unless there is a credible control group that provides a counterfactual. RCTs overcome the limitations of other methods where unobserved factors can influence the result of an evaluation. By providing a credible counterfactual, RCTs offer more accurate and persuasive evidence, robust enough to change people’s views on the impact of a particular programme. Therefore, they are more likely to influence the choices that are made, leading to better decisions.

How feasible is it to run RCTs in science, innovation and business policies? It’s true that RCTs haven’t been widely used to test science, innovation, entrepreneurship, and small business programmes, often due to fears that experiments are too complex or disruptive. However, we’ve helped hundreds of policymakers overcome the challenges of running experiments, as there are many ways and reasons to become experimental.

How can RCTs be used in this policy area? RCTs are flexible instruments that can be used to address lots of different questions. Some RCTs are small-scale and can be easily embedded into an organisation’s activities at little or no cost, while others are complex, large-scale and require careful planning and resources. The main uses of RCTs are:

- Programme evaluation, estimating the causal impacts of a programme or comparing the cost-effectiveness of different versions of the programme. For instance, when rolling out an innovation funding scheme for SMEs, an experiment can be used to test the impact of the scheme, but also to test whether adding a management coaching element on top of it makes the funding more effective.

- Process optimisation, including the use of simple A/B testing, to improve the processes used in the delivery of a programme. For instance, an experiment can be used to test small tweaks in a newsletter in order to increase the number or quality of applications for a business support programme.

- Problem diagnosis, using experimentation to identify the underlying causes and mechanisms that drive individuals’ and firms’ decisions, which can then justify and inform policy interventions. For instance, an experiment can be used to identify whether reviewers assessing funding applications are biased and rate applications from better known universities or companies higher than they should.

Where can I find examples of RCTs in this field? IGL curates an online database that provides information on RCTs related to science, innovation, entrepreneurship and business policies, searchable by topic.

Is doing an RCT very expensive? Doing RCTs is not more expensive than conducting other forms of evaluation, and some RCTs can be done at little or no cost. Often the most expensive part of a trial is the programme itself — a cost which the organisation is presumably incurring in any event. Data collection can also require substantial resources if administrative data is not available, but this is true of any type of evaluation regardless of the method used (as data is required in any case). Beyond programme and data collection costs, the actual costs of running an RCT are relatively low. In addition, researchers from the IGL Research Network are often willing to collaborate at little or no cost if the trial helps advance their research agenda. Trials can often pay for themselves, either by saving the programme’s future cost if it proves to be ineffective, or by significantly improving their effectiveness with simple tweaks. Moreover, the structure that trials impose can be beneficial even on its own, because it leads to better designed programmes and more careful execution.

Aren’t RCTs unethical? It is always important to consider ethical implications when designing an RCT, but it is useful to remember that RCTs are widely accepted in much more difficult contexts, like testing new life-saving drugs. While some may argue that it is unethical to withhold support to some participants, an implicit assumption behind this criticism is that trials involve denying some potential recipients an intervention that would benefit rather than harm them. However, this cannot be taken for granted. Rolling out programmes without knowing whether they are beneficial or harmful is a risk worth preventing. Even for those interventions for which “harm” is extremely unlikely, there is still an “ethical” case to be made in favour of experimentation (rather than against it). Spending taxpayers’ money on a programme that is ineffective deprives more effective programmes of funding, so RCTs can help elucidate whether we are making a good use of limited public resources. Moreover, in many circumstances an RCT does not require that the control group receives nothing at all — often different versions of the same programme are pitted against each other, with all participants receiving part of the intervention in some form. Alternatively, when programmes are rolled-out progressively (rather than for everyone at once) due to budget or capacity constraints, the order in which the programme is introduced can also be randomised. In this case, no one is denied the programme, and those required to wait may ultimately benefit by getting a more developed and therefore more effective intervention.

Isn’t it unfair or inefficient to use a lottery to select participants? There is sometimes a fear that undeserving applicants may benefit from a programme when conducting an RCT, and those that would benefit the most will not. Budgets are often insufficient to support all deserving applicants, so the question is “What is the most appropriate method of allocating limited funding?” In some circumstances a lottery can be a fairer and more efficient approach to select participants than other systems frequently used, such as first-come first-serve criteria or some proposal scoring systems. Ultimately, lotteries can be designed in different ways to accommodate an organisation’s criteria. For instance, RCTs do not require providing funding to undeserving applicants, because those can be screened out prior to conducting the lottery. Similarly, best-ranked applications might be funded directly, with the lottery being used instead to select among similarly-ranked middle-tier applications.

Don’t voters dislike experiments? Recent studies in several countries have demonstrated that voters strongly support policy experimentation. In addition, several governments engaged in policy experimentation exemplify that it is possible to get buy-in from the key stakeholders involved (including programme participants) using a careful communications strategy that demonstrates the value of experimentation.

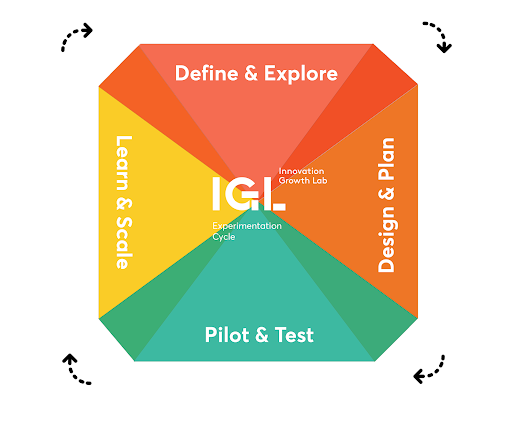

How do we successfully develop an experiment? Running experiments can be challenging, as they require a set of conditions and procedures. At IGL, we follow a four-step process for success:

- Define & Explore: Identify the problem and explore areas of intervention where an experiment could help.

- Design & Plan: Assess the design of the intervention to ensure it can be evaluated, and put the structure in place for a successful experiment;

- Pilot & Test: Start with small-scale tests before moving on to larger experiments;

- Learn & Scale: Take what has been learned from the experiment, apply it, share it, and continue experimenting.