Blog

Venture growth strategy: How do entrepreneurs spend their time?

7 July 2022

Entrepreneurs are problem-solvers at heart: They search for problems that need solving and try to build organisations that can sustainably replicate the problem-solving function. Such is the nature of entrepreneurial opportunities – a logical nexus between a problem and a corresponding solution so that the value of solving the problem is greater than the cost of providing the solution.

From an economic perspective, the objective function of entrepreneurs is to maximise the value of the opportunity they commit to pursuing. First, by exploring opportunities with large values relative to their costs. Next, once committed to a given opportunity, managing an organisation to exploit the opportunity as efficiently as possible.

Organisational ambidexterity is the capability to execute both exploration and exploitation activities simultaneously and effectively. It is a crucial capability for the long-term survival of organisations, yet extremely challenging to master.

How do entrepreneurs spend their time on exploration-led or exploitation-led growth strategies? Are there differences in growth strategies across companies with different growth potential or types of founders? Does supporting entrepreneurs in pursuing specific growth strategies affect the returns to the time spent growing their businesses?

An experiment financed by the Innovation Growth Lab aims to dig deeper into these questions. Aldea Experimenta, a program funded by iNNpulsa Colombia, and led by the Cali Chamber of Commerce, is being implemented in coordination with other 11 Chambers of Commerce of the country, and two consulting firms, to support high-potential entrepreneurs. So far, the baseline application to the program is already providing a window into growth strategy choices by entrepreneurs.

Growing pains

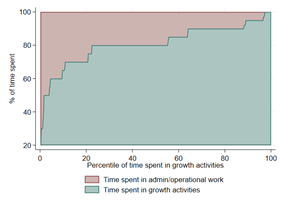

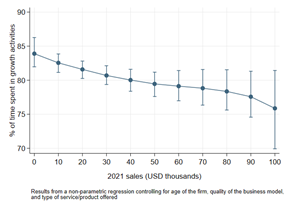

To assess how much time entrepreneurs in Aldea Experimenta spend pursuing different growth strategies, we began by asking lead founders to describe how they split their time between the pursuit of growth and administrative tasks. By this, we mean both exploratory and exploitative strategies by growth activities, like looking for new markets, networking, implementing new organisational routines, and analysing market data. Administrative tasks include more routine everyday jobs, including paying providers, drafting reports, paying taxes, and administrative meetings. Figure 1 illustrates some of our findings.

Panel A shows that the median entrepreneur spends 20% of their time on administrative tasks instead of growing their firms. Panel B shows that those administrative tasks become even more time-consuming for company leaders as firms grow. Furthermore, one bottleneck in spending more time pursuing growth is a lack of delegation: lead founders do not delegate tasks despite hiring more employees or having other business partners. From a list of ten administrative functions, 80% of interviewees reported involvement with 7 or more of those tasks.

Fig 1. Growth versus administrative time dedicationPanel A. Time distribution of leader Panel B. Time spent in growth activities by sales level

A bird in the hand or two in the bush?

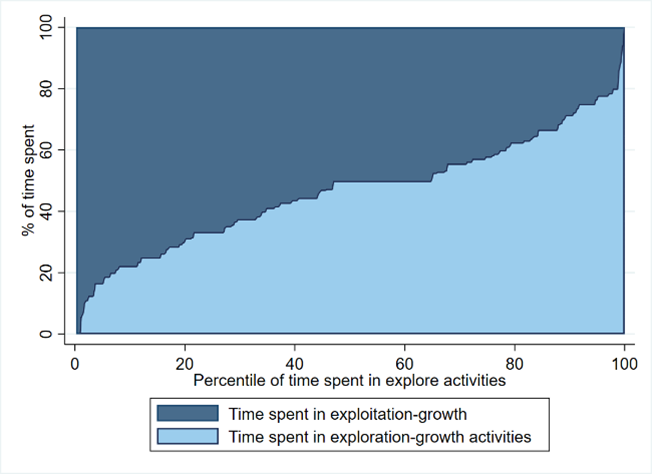

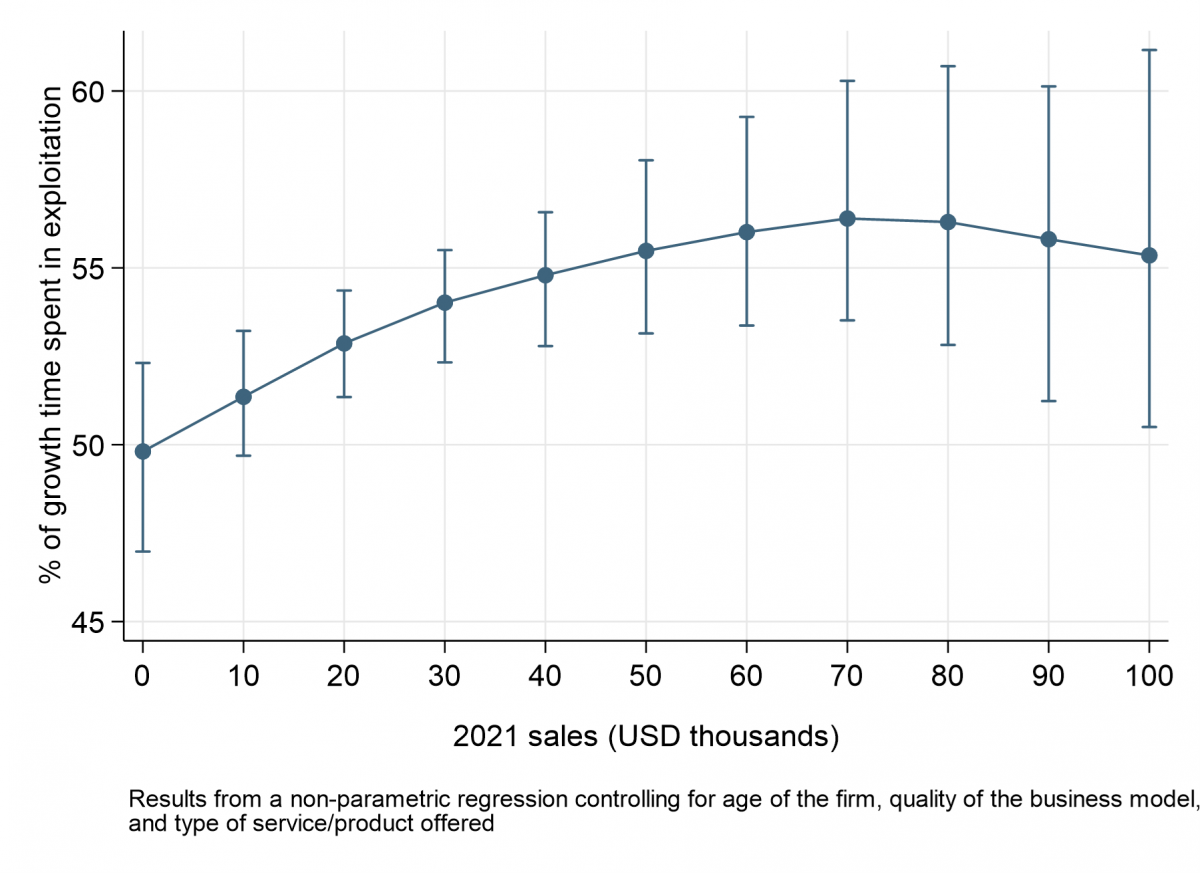

Given the time constraints facing entrepreneurs in Aldea Experimenta, how do lead founders spend their time devoted to growth? Do they focus on exploratory or exploitative activities? Figure 2 shows heterogeneity across entrepreneurs in splitting their time between growth strategies. There is an apparent segmentation: half of the entrepreneurs devote more of their growth time to pursuing exploratory activities, and the other half to exploitative activities.

The segmentation is related to heterogeneity in growth strategies across business sizes. As firms grow, entrepreneurs appear to spend more time improving the exploitation of a given opportunity rather than exploring new opportunities. This pattern does not mean that entrepreneurs in growing firms do not see the value in exploratory activities. Three out of four entrepreneurs mention that if they could free some of their time dedicated to administrative tasks, they would devote such time to pursue growth using exploratory activities.

Also, this evidence does not imply that entrepreneurs fulfil all their exploitation activities and goals by spending more time on them. Only 36% of entrepreneurs had defined or updated their business indicators in the last six months, 42% had created or implemented quality control processes, and 43% had trained their employees in the existing technology in their firms.

Fig 2. Growth versus admin time dedicationPanel A. Time distribution of leader across growth-strategies Panel B. Time spent in exploitation-led growth activities by sales level

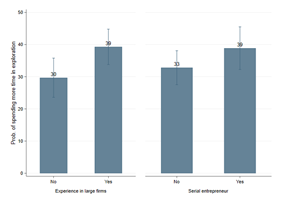

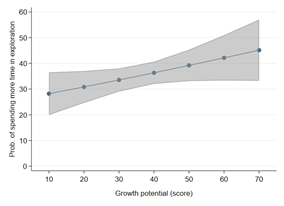

So, who are the entrepreneurs that spend more time on exploration-led growth relative to exploitation-led growth? Figure 3 shows an interesting pattern between growth strategies and entrepreneurial experience. Serial entrepreneurs and those who have working experience in large firms are more likely to dedicate more time to exploration activities. Also, businesses with higher growth potential (assessed by external judges and ventures’ characteristics) appear to devote more time to exploration activities.

Fig 3. Conditional probability of spending more growth time in exploration Panel A. by characteristics of the leader Panel B. by growth potential score

Opening the black box of entrepreneurship support programs

Governments and development agencies have implemented several programs to help entrepreneurs overcome different constraints they might face during the growth stage. However, interventions tend to provide support to firms without distinguishing growth strategies. We still lack theories and evidence about what works in supporting high-growth entrepreneurship and who benefits most from these support programs.

Our intervention will allow us to disentangle some of those questions by randomly supporting entrepreneurs in pursuing either an exploratory or exploitative growth strategy. In this experiment, we match 150 entrepreneurs in Colombia with consultants that help them implement distinct growth strategies. All entrepreneurs receive help from consultants. But they are randomly assigned to two groups that differ in the type of growth strategy that consultants provide. The first is an exploration-focused intervention where consultants support entrepreneurs in exploring new markets, new products, and new business models. The second is an exploitation-focused intervention where consultants support entrepreneurs in implementing routines and processes that allow them to exploit their existing products, markets, and business models. We assign consultants to groups based on their business mindset, using tests to measure their exploration versus exploitation predisposition.

Does an exploration-focused intervention allow entrepreneurs to test and pivot their business faster to find the business model that maximises value in the market? Or is an exploitation-focused program more effective at helping entrepreneurs capture the value of the opportunities they have already identified? Do the effectiveness of these interventions differ by the innovativeness of the business or characteristics of the entrepreneur? Are there complementarities in the type of support received and the growth strategy pursued by entrepreneurs before the intervention?

We expect to have the first set of results by the end of the program this year and annual follow-ups afterward.