Blog

A symphony for policy experimentation: The innovation quartet

24 September 2019

The power of collaboration

In a world of increasing automation and changing occupation schemes, interpersonal skills undoubtedly emerge as key determinants in our ability to cope. One of these essential skills is the ability to foster partnerships and collaborative problem solving, linked to traits such as empathy and adaptability. As our colleagues from the Inclusive Innovation team summarised it in a recent paper, “Theories of collective intelligence and cognitive diversity show that more diverse groups are better at solving problems.” Collaboration is also key for innovation, since it allows us to look at challenges and opportunities from a different angle and come up with fresh ideas and a coordinated vision for change. Finally, collaboration is essential for our ability to put these ideas to the test: partnerships in policy experimentation allow players to combine their unique knowledge, skills and resources.

While collaboration may sound like a simple quest, any of us who have ever worked in teams and tried to agree on a joint vision (or timeline) know that translating this into practice can be anything but straightforward. And while it may be challenging to foster collaboration between individuals, it is even trickier to create partnerships at organisation level, especially when these organisations are very different in nature, eg linked to different disciplines, sectors, or ecosystems. So what makes collaborations an undertaking worth pursuing despite the difficulties?

We can gauge the potential gains from cross-sectoral collaborations by reviewing a recent successful example that involved partners from across the ecosystem. Our flagship example, presented later in detail, is the fruitful partnership between an NGO, MicroMentor (a programme of Mercy Corps), and academics from the University of Oregon and the Old Dominion University. This collaboration resulted in a randomised controlled trial, supported through the IGL Grants Programme, that unpacked the black box of matchmaking on an online mentoring platform for small businesses. 1

The innovation ecosystem: players and key strengths

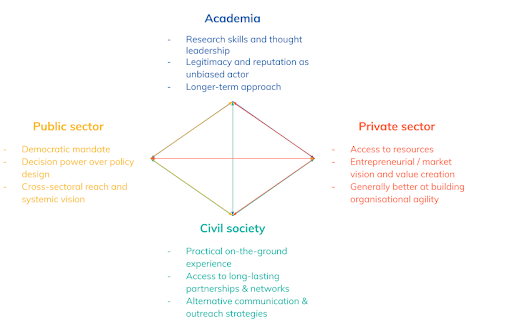

As mentioned above, what makes this idea of partnerships and collaboration so attractive is that it allows players to take a fresh look at challenges and come up with innovative ideas that would otherwise have never seen the light of day. Obviously, the details will differ from one case to the other. However, attempts to paint a very general picture of the players in the innovation ecosystem (often referred to as the quadruple helix,) including their key strengths and added value, summarise the main aspects in the figure below:

While somewhat simplified, we hope this figure conveys a clear message: every node of this quadruple helix has its unique contributions that are complementary to each other, and collaborations between the nodes can lead to valuable synergies.

Example: Partnership between MicroMentor and University of Oregon

We can observe these complementarities in practice through the lens of a successful collaboration between MicroMentor and the University of Oregon and the Old Dominion University. Emily Joy (Business Solutions Manager at MicroMentor) and Saurabh Lall (Assistant Professor at the University of Oregon’s School of Planning, Public Policy and Management) shared the details of how they created a strong and mutually beneficial partnership, how they designed and ran a trial together, and what they gained from the collaboration.

Saurabh first came into contact with MicroMentor through the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs – but it wasn’t until a year later, when he moved to Oregon and reached out to MicroMentor’s Portland office, that they started discussing the potential for collaboration in more detail. The timing was perfect, as MicroMentor had just started thinking about revising their impact measurement strategy. As Emily put it, “We came to this project with the mindset that it was time to do major house cleaning, and to reinvent what monitoring and evaluation looks like for Micromentor. We were ready and willing to make changes. Having advice and counsel from a panel of experts at this time has been beyond valuable.”

Their fledgling partnership soon received a massive boost in the form of a seed grant from the Kauffman Foundation and the Social Enterprise @ Goizueta Center at Emory University. The money itself was very helpful (it allowed MicroMentor to spend time on programming and data requirements), but equally important was the structure that the grant application imposed on the collaboration: it helped Emily, Saurabh and their teams narrow down their list of options and sharpen the focus of their research. Their well developed project outline then allowed them to successfully apply for a larger grant offered by the Kauffman Foundation and Argidius through the IGL Grants Programme.

When choosing among several possible research questions, the team prioritised questions that directly addressed the needs of MicroMentor over exciting, but from the organisation’s perspective “esoteric” inquiries. In Saurabh’s words: “As researchers, we come in with some ideas – but it is useful to recognise the constraints that MicroMentor operates within, and where there is flexibility therein, and then work with that to develop a useful experiment: useful as in generating knowledge from a research perspective, but also useful for the partner in terms of things they could actually implement – useful from a practical perspective.” In return, MicroMentor ensured that the project was owned and carried forward: part of Emily’s time has been explicitly dedicated to monitoring and evaluation.

Probably unavoidably, the partners experienced a few hiccups during the realisation of the project. The project took significantly longer than expected; glitches in the technology rendered some of their early data useless; and a pilot revealed that one of their planned interventions, though theoretically well-motivated, wasn’t effective in practice. What helped them through these hiccups? Emily and Saurabh both identified excellent communication between the collaborating partners as the key ingredient. They have maintained an open line of communication throughout, and held (bi-)weekly project update meetings where the research team shared insights from analysing historical data and preliminary findings from their trial. These exchanges allowed MicroMentor to learn from the collaboration early on, without having to wait for the final results and the peer-reviewed and published paper. The discussions also provided a reality check for the researchers, improved their understanding of the context that they were working in, and made them more confident in their interpretation of the results.

The benefits that MicroMentor experienced from the collaboration went well beyond the direct results of the trial. The partnership allowed them to improve their platform, training and data management system; it inspired them to conduct small A/B tests and even to adjust their strategy in light of the new findings – they thus saw gains they would not have been able to predict at the outset. According to Emily, “the collaboration has led to new opportunities and interest from grantors, but also had a great impact internally, within the Mercy Corps organisation, that finally, after 10 years of being an online platform, we have a team of external evaluators who help us validate our outcomes and set in motion a standardised test practice moving forward.” The team of researchers also uncovered a treasure trove of opportunities for further scientific inquiry. In Saurabh’s enthusiastic words: “Honestly, we are just scratching the surface of what we could learn from MicroMentor.”

****

In the second part of our series, to be published in a few weeks, we will discuss the systemic challenges that stand in the way of partnership formation, and ways the government can help overcome them. In the meantime, we recommend the following insightful related content:

- Rachel Glennerster on what makes a good implementing partner

- Duncan Green’s The NGO-academia interface: Realising the shared potential

- Philipp Lottholz & Karolina Kluczewska on researcher-practitioner collaborations

- Nava Ashraf’s call for climbing down from the ivory tower

- And some great personal stories from the World Bank’s implementing and government partners

***

Read more:

Intro: A symphony for policy experimentation

Part 2: Conductor wanted

- 1. Needless to say, there are several other examples out there that provide real-life evidence on how partnering with an institution that may not fall into the list of traditional collaborators can develop new shared value and have enormous mutual benefits. Just to mention a few: Uber partnered with researchers from Yale School of Management and UCLA’s Anderson School and demonstrated that the drivers’ flexible scheduling actually made them better off; an Indian NGO, J-PAL and the government successfully developed and scaled an innovative pedagogical approach that improved students’ learning outcomes; and the UK government’s collaboration with the Behavioural Insights Team and academics from Warwick and Chicago proved that behavioural science-informed nudges can reduce tax avoidance.