Blog

Mission-oriented innovation policy: how can experimentation help?

11 July 2019

Mission-oriented innovation policy is back on the agenda, gaining more and more traction among both innovation policymakers and practitioners. The European Commission has embraced the concept of “missions” in Horizon Europe, and many innovation agencies are also planning to launch mission-oriented programmes in the near future, if they haven’t already done so.

Yet, despite all this talk about missions, there is very little knowledge, practical guidance and prior experience on how to successfully implement them.

Yet, despite all this talk about missions, there is very little knowledge, practical guidance and prior experience on how to successfully implement them. We are still missing a “how to” guide to deliver missions, and face many unanswered questions on how to successfully implement them.

Adopting a more experimental mindset is one of the ways to start getting some of the answers we need. The question is how: is it possible to embed an experimental approach in the design and implementation of mission-driven innovation policies? What would the benefits be? Where to start?

This is what we were asked to discuss at this year’s Taftie Annual Conference in Luxembourg, which brought together innovation agencies from across the continent and beyond to discuss ‘Mission-oriented Research and Innovation’.

In this blogpost we want to share some of our current thinking on the interaction between missions and experimentation. We also want to hear your views and learn from people working on missions – so please feel free to get in touch!

What is mission-oriented innovation policy?

The European Commission defines it, in uncharacteristically succinct terms, as ‘an approach to policymaking which means setting defined goals, with specific targets and working to achieve them in a set time’. In her report on the topic for the Commission, Mariana Mazzucato (perhaps the biggest champion of missions) defines them as ‘systemic public policies that draw on frontier knowledge to attain specific goals or “big science deployed to meet big problems”’. The classic example is the moonshot – a concerted, cross-sector effort mobilising large resources with a clear goal in mind.

In preparing for our Taftie presentation, we tried to understand what this means in practice: what are the actions a mission-driven innovation agency must take? We found that there is very little work describing in detail the actual stages involved in mission-oriented policymaking1.

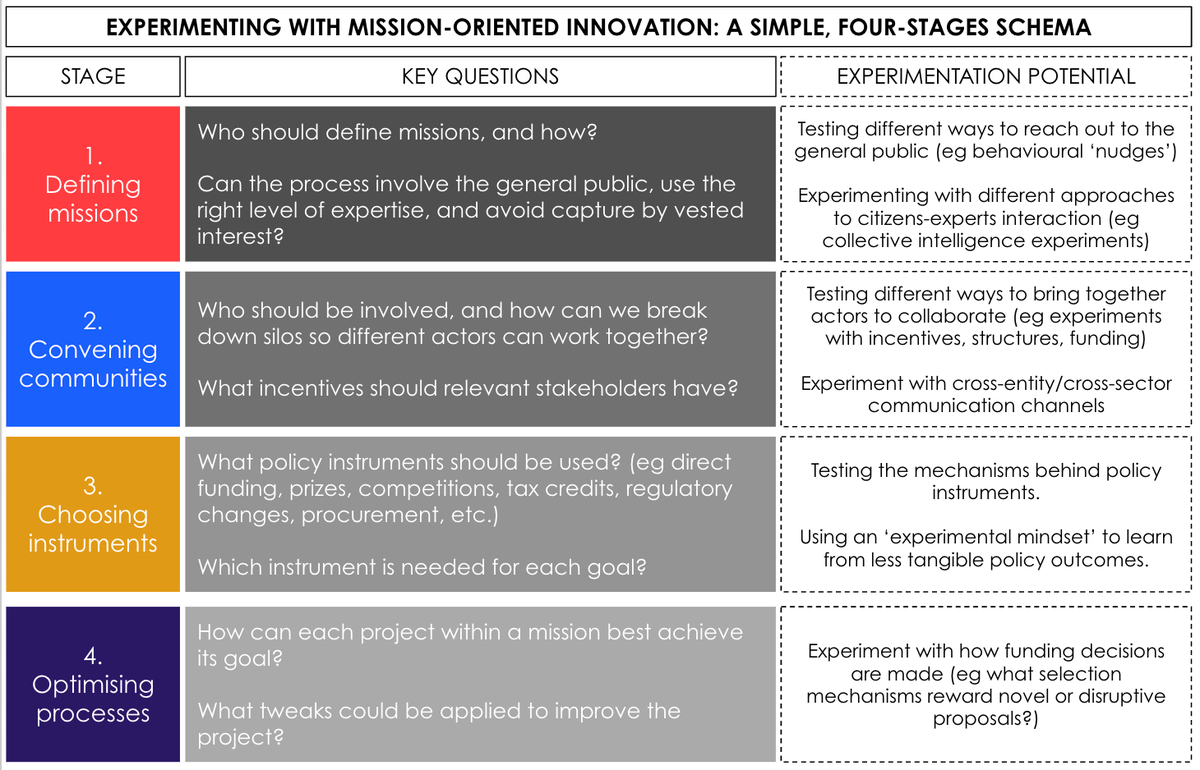

Of course, this is a complex topic and not every mission will be implemented in the same way. Yet we feel it is useful to have a simple, schematic way of summarising the key steps of a mission:

- Defining missions: most of the leading sources on the topic stress the need for missions to be concrete and ‘granular’, while also incorporating input from the general public.

- Convening communities: missions require bringing together diverse actors from multiple sectors to collaborate.

- Choosing the right instrument mix: because of their scale and cross-cutting nature, missions might involve funding calls, changes to regulation, direct support, etc. A key issue is what combination of policy schemes works best.

- Optimising processes: like any public (or for that matter, private) programme, missions require complex operations that are hard to get right at first. Thus, regardless of what policy mix is ultimately chosen, each aspect of a mission needs to be constantly tweaked, learning from past mistakes and successes.

This is, naturally, very simplified, but it helped us sketch out how experimentation can be applied to missions. We are keen to hear of any other attempts to describe the practical steps required to take on mission-oriented innovation.

What is experimentation?

At IGL, experimentation is our bread and butter – we’ve spent years arguing that innovation policy should make greater use of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), and take on an experimental mindset more broadly.

That is why we were pleased to read, across much of the literature on missions, about the need to have a ‘culture of experimentation’ and that we should be ‘experimenting with new ways of policymaking’.

And yet it is not always clear what is meant by an experiment. In fact, when people talk about experimenting often they mean ‘trying something new’. However, we believe that experimentation requires learning:

There are of course a number of ways to experiment. These can be broken down into:

- Experiments for exploration and discovery. These experiments could be about uncovering and testing assumptions to further our understanding of an issue; or about testing the potential and feasibility of a new idea.

- Evaluation or ‘what works’ experiments. These are about improving an idea or a programme by experimenting with its processes; or about evaluating the impact of a programme.

A key idea is that RCTs are only one tool in the toolbox – but their use is not restricted to impact evaluation experiments. In fact, when well designed, they can be used to uncover assumptions, explore potential and improve processes.

How can experimentation be used in the context of missions?

So how can these two elements – missions and experimentation – come together? We think there is potential to experiment at each of the four steps described above:

- Defining missions. While missions could potentially be selected top-down, there is agreement that it is better to involve the wider public to identify priorities and choose among them, even if the final decision is ultimately a political one. But how can we know what is the best way to do that? One approach could be to experiment with public outreach to ensure as many people as possible learn about, and get involved with, the selection process; this could take the form of experiments with nudges, such as those run by our partner at BEIS to engage with firms and business mentors. Other experiments could be run to understand the most fruitful ways for citizens and experts to interact.

- Convening communities. Again, there are a number of political decisions to be made regarding who should be involved. Once that’s decided, however, experiments can be really helpful in driving the process forward. For instance, experiments could be run to compare different ways of bringing people together to collaborate (eg from simply being brought together for a short joint session, to hands-on workshops focused on how they can collaborate, to offering funding for collaborative projects).

- Choosing the policy instrument mix. This is probably the most difficult point, as comparing completely different policy approaches is not quite possible in a classic experimental way. Of course, experiments can be used to understand whether individual instruments work, which can help decide which one to pick. Moreover, well-designed experiments can tease out the mechanisms behind ‘what works’. Yet there is no simple way to ‘robustly’ evaluate dynamic choices of policy instruments. We believe an experimental mindset can help policymakers explore new possibilities while learning from ‘good failures’ – but there remains much to learn about this approach. We are open to hearing more about how others are thinking about bringing robust monitoring & evaluation techniques to this question, since it is definitely an important one.

- Optimising processes. Whatever policy mix is agreed, each individual policy tool being used involves many decisions and choices, so can be tinkered with to try and maximise its impact. This is not just about conducting impact evaluations to run cost-benefit analyses; it can focus on a variety of goals, depending on the specific process or policy at hand. Funding calls are a clear example: despite being one of the most used policy instruments, not enough experimentation is done to better understand what works best at each stage. Possible experiments span the ‘customer journey’ of a grant scheme: how can we get more and/or better applications? How does our assessment process affect what type of projects we fund? How do other procedures affect the grants’ impact? This is an area where experiments could do a great deal in driving innovation forward.

What’s next?

This is just the beginning of our thinking on this topic, which is becoming increasingly more important for policymakers in innovation and industrial policy.

There are lots of other elements to consider, and RCTs are only one piece of the puzzle. Experimentation means much more – it is also a mindset, an organisational culture and an approach to failure. We are also aware that experiments sit within a family of methods, and we can all learn from adopting as many tools as there are inside the policy toolbox.

We are keen to find out what other people and organisations are thinking and doing with experimentation in mission-oriented innovation. If you have any thoughts or questions, share them with us at [email protected].

- 1.A possible exception is this new report by the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, which sets out a number of steps; however, it is focused on the UK and its industrial strategy.