Blog

The long-term impact of Dutch innovation vouchers: Back to the future with randomised controlled trials

30 January 2020

Theo Roelandt, Henry van der Wiel

For more than twenty years, innovation vouchers have been used by policymakers to improve the competitiveness and growth of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) by encouraging innovation through the exchange of knowledge and collaboration with public knowledge institutes.

Based on a randomised controlled trial (RCT) and a unique longitudinal data set, our studies show that for the Netherlands, and in the long run, small policy interventions like this can structurally change firms’ behaviour and innovation performance. 1

Innovation policy can change firm’s behavior

In the Netherlands, innovation vouchers were distributed among applicant firms in 2004 and 2005 as a policy innovation instrument to stimulate the interaction between SMEs and public knowledge institutes. By doing this, policymakers tried to find a way to bridge the gap between two different and poorly connected worlds: knowledge & technology suppliers on the one hand (such as universities), and SMEs on the other. In order words, they tried to fix an existing mismatch in the innovation system that hindered knowledge diffusion, and to do so they took the risk of trying something simple that might work (or might not at all).

By doing this, policymakers tried to find a way to bridge the gap between two different and poorly connected worlds: knowledge & technology suppliers on the one hand (such as universities), and SMEs on the other.

The results of our studies, discussed in more detail below, show that a small and simple policy intervention can have a large consequence over time. But why? The main answer to this question is that innovation vouchers can change firms’ behaviour and business strategy. For most firms participating in the innovation voucher scheme, it was their first contact with suppliers of new knowledge and technology. Beforehand, most small companies were unaware of what new technology and starting up an innovation project might bring them in terms of future benefits. Their first R&D project, successful or not, created firms’ awareness that new technology and innovation might, and can, improve business performance and that continued R&D and innovation activities in the future (with or without their initial partners) could help in surviving competition and in creating new business opportunities. In essence, what the vouchers created was a starting point for a changed strategy.

What did we find?

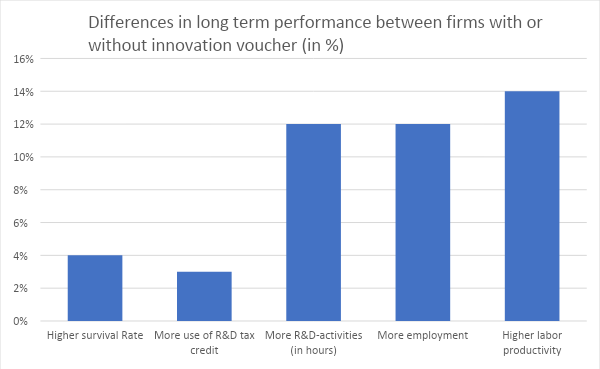

The Dutch innovation vouchers were allocated randomly by means of lottery among applicant firms, allowing us to assess whether this innovation instrument works or not. In principle, any difference between the firms with a voucher and firms without a voucher is the result of the intervention. To estimate the long run impact, we merged data of both the treatment and the control group with their long-term performance data collected by Statistics Netherlands over the period 2004-2016. This is quite unique worldwide. We found that innovation vouchers have had a positive impact on a number of key performance indicators in the (medium) long term. The more detailed results are as follows:

-12 years after the RCT, firms in the treatment group compared to firms in the control group have a higher business survival rate (plus 4%), use the labour-based R&D tax credit scheme more often (plus 5%), have a higher level of R&D activities (plus 12% more hours) and offer more employment (plus 12%);

-Although the effects are structural, they already begin to appear in the short term (within 2 years after the lottery) and remain at the same level in the mid- and long-term;

-Finally, we also found a positive but not significant direct effect on firms’ productivity level, but for this efficiency output indicator, the time period to observe a significant impact might still be too short. However, based on additional analysis, it turned out that if a firm follows up the initial voucher by setting up a structural R&D activity the impact on firms’ productivity is statistically significant.

What’s new?

Our studies bring two new contributions to the existing knowledge on the impact of innovation vouchers on firms’ behaviour and performance using an RCT-trial research design.

First, by linking the data for all applicants to the national business register of Statistics Netherlands (containing actual firms’ performance data) we created a unique new data set and in doing so, a unique opportunity to measure the causal effect of a voucher over a long period of time. The RCT enabled us to compare similar firms in the treatment and control group (Bravo-Biosca, 2019) and consistently measure short, medium- and long-term impact. More important, the merged data made it possible to base our analysis on actual firms’ performance rather than relying on businesses to self-report.

Second, our study provides the first causal evidence that innovation vouchers can have a structural long-term impact on actual firms’ behaviour and performance. So far, evaluations in different countries have indicated that in the short run these vouchers help stimulate innovation activities among SMEs (Cornet et al. 2006, 2007; Potts and Morrison, 2008; SQW, 2014; Sala et al., 2016; Bravo-Biosca, 2019). But so far, most scholars assumed that a long-term impact was not very likely to appear: these kind of policy intervention, awarding a very small subsidy by awarding innovation vouchers, is considered to be too small to change firms’ attitudes towards innovation. And as a consequence, these scholars assume that vouchers are not likely to have any structural and long lasting effect on firms’ innovation behaviour (Veugelers, 2015; Virani, 2015). However, empirical evidence supporting this assumption is limited. In most cases these evaluations were conducted within one or two years after the innovation vouchers had been awarded and most of the results were based on self-reported evidence from SMEs using the vouchers. Next, only a small number of voucher schemes were RCT-like experiments in which a treatment group can be compared with a similar control group. Langhorn (2014) discussed the UK and the Netherlands as examples where innovation vouchers have been awarded by means of a lottery. As far as we know, the only comparable study using a RCT-like experiment combined with longitudinal information is an evaluation of Nesta’s Creative Credits in the UK by Bakhshi et al. (2015). Like the Dutch innovation vouchers these credits were also awarded by means of a lottery among applicants. For the collection of the longitudinal data they used a mixed-method strategy including both quantitative and qualitative data based on surveys of SMEs of both the treatment and the control group.

Concluding remarks

Changing how the innovation ecosystem functions, creating new incentives to boost the different actors to exchange knowledge and to co-operate in R&D projects, and changing business strategy and interaction processes can create high “bang for the buck” in the long run. Policymakers, and politicians as well, must be patient, as it is all about changing behaviour and new interaction patterns. And that takes time. Innovation vouchers can, if well designed, help to create that starting point for a transition to a new world of SME business practices, like in childhood, when we set our first independent steps and learn to walk without help, paving the way to a world full of opportunities.

With thanks to our colleagues at Statistics Netherlands and Netherlands Enterprise Agency.

References:

Bakhshi, H., Edwards, J. S., Roper, S., Scully, J., Shaw, D., Morley, L., & Rathbone, N. (2015). Assessing an experimental approach to industrial policy evaluation: Applying RCT+ to the case of Creative Credits. Research Policy, 44(8), 1462-1472.

Balabay, O., L. Geijtenbeek, J. Jansen, O. Lemmers and M. Seip (2019) Het langetermijneffect van innovatievouchers voor mkb-bedrijven op bedrijfsresultaten (only in Dutch). Published at CBS and RVO.nl and on www.bedrijvenbeleidinbeeld.nl

Balabay, O., L. Geijtenbeek, J. Jansen, O. Lemmers, Th. Roelandt, M. Seip and H. van der Wiel (2020, forthcoming, to be published), Crossing the bridge towards R&D and innovation: the long-term effect of Dutch innovation vouchers (working paper).

Bravo-Biosca, A. (2019). Experimental Innovation Policy (No. w26273). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Cornet, M., Vroomen, B., & Van der Steeg, M. (2006). Do innovation vouchers help SMEs to cross the bridge towards science? (Vol. 58). CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis.

Cornet, M. F., van der Steeg, M., & Vroomen, B. (2007). De effectiviteit van de innovatievoucher 2004 en 2005: effect op innovatieve input en innovatieve output van bedrijven. Centraal Planbureau.

Langhorn, K. (2014). Encouraging entrepreneurship with innovation vouchers: Recent experience, lessons, and research directions. Canadian Public Administration, 57(2), 318-326.

Lemmers, O., Th. Roelandt, M. Seip, H. van der Wiel (2019), Innovatievouchers zorgen structureel voor meer innovatieactiviteiten. Economisch Statistische Berichten, October 14th.,

Potts, J., & Morrison, K. (2008). Nudging innovation: fifth generation innovation, behavioural constraints and the role of creative business. Nesta

Sala, A., Landoni, P., & Verganti, R. (2016). Small and Medium Enterprises collaborations with knowledge intensive services: an explorative analysis of the impact of innovation vouchers. R&D Management, 46(S1), 291-302.

SQW (2014). An evaluation of the Invest NL innovation voucher program: A final report to Invest NI. Available from: http://www.sqw.co.uk/files/3414/2188/1186/ innovation-vouchers-final-evaluation-report-nov-2014.pdf.

Veugelers, R. (2015). Mixing and matching research and innovation policies in EU countries (No. 2015/16). Bruegel Working Paper.

Virani, T. E. (2015). Do voucher schemes matter in the long run? A brief comparison of Nesta’s Creative Credits and Creativeworks London’s Creative Voucher schemes. Creativeworks London Working Papers.

- 1.Theo Roelandt is economist and the Chief Analyst of DG Enterprise & Innovation of the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Change (DG E&I/EZK). He is chairing the Policy Analysis Team (BAT) at the ministry, including the joint research projects with Statistics Netherlands and The Netherlands Enterprise Agency. Henry van der Wiel is economic advisor at DG E&I/EZK.