Blog

IGL2019: Gender and innovation

7 June 2019

At IGL2018, we were compelled to reckon with a large and persistent gender gap in innovation – and so this year, we asked experts how we could close the gap. Sofia Bapna from the Carlson School of Management and Rembrand Koning from the Harvard Business School presented some answers based on their latest research at the IGL2019 Research Meeting in Berlin.

Last year at the IGL2018 Global Conference in Boston, John van Reenen presented a disheartening finding: at the current rate of change, it will take 118 years to reach gender parity among patent holders.

Last year at the IGL2018 Global Conference in Boston, John van Reenen presented a disheartening finding: at the current rate of change, it will take 118 years to reach gender parity among patent holders. A lack of exposure to innovation, he argued, keeps talented women from fulfilling their potential as innovators. To drive home the idea that as a society we are missing out on ideas and talent from under-represented groups, he and his co-authors coined the terms “lost Einsteins” and “lost Marie Curies”.

But would we even recognise a new ‘Marie Curie’ if we saw one? New research documenting gender bias in the evaluation of ideas suggests that the answer is often “no”. Using data from applications to the Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant programmes, researchers found that female grant applicants were as successful as men when peer reviewers assessed the quality of their proposals alone, but not when reviewers were also asked to evaluate the caliber of the scientist. In addition, a study of approximately 2.7 million US patent applications shows that female inventors tend to have less favourable outcomes (lower acceptance rates and fewer citations) than men. Strikingly, these results seem to be driven by female inventors with common first names that easily allow examiners to infer their gender. Moreover, investors tend to prefer male entrepreneurs over women – even when their pitch is identical. These findings suggest that even when women come forward with their ideas, they often fare worse in terms of financing and commercialisation than male inventors.

Tackling this bias in evaluation and funding is key to increasing the share of female innovators – but doing so is easier said than done. A blinded review process (where applicant gender is hidden from the evaluators) seems like an obvious fix, and has been shown to reduce gender bias in other settings. However, a recent study of grant proposals submitted to the Gates Foundation has documented a gender gap in scores despite blinded review. Adding more women to scientific evaluation committees does not necessarily improve female candidates’ outcomes either.

In a clever experiment on a crowdfunding platform, Sofia and her co-author provided potential investors with information about a venture with two co-founders, randomly showing investors either the male or the female founder’s name alongside the characteristics of the venture.

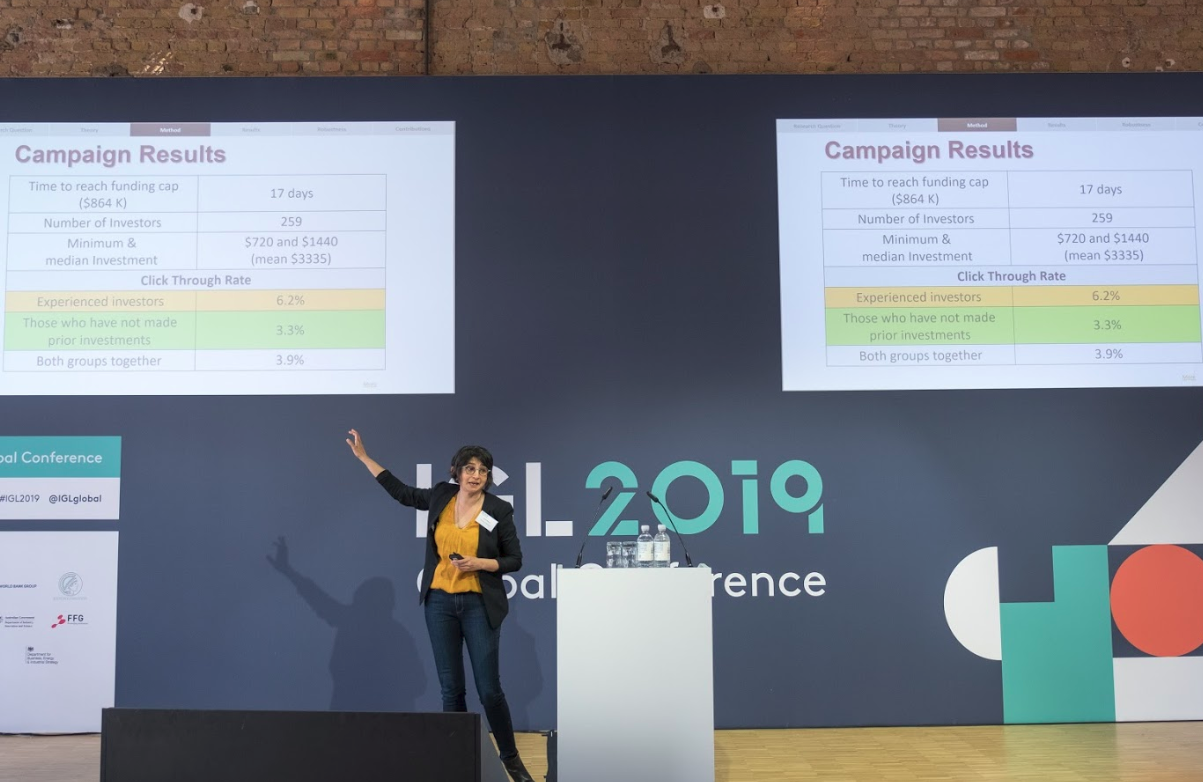

One possible solution, examined by Professor Sofia Bapna, is to radically extend the group of evaluators who are involved in the funding decision, through equity crowdfunding. In a clever experiment on a crowdfunding platform, Sofia and her co-author provided potential investors with information about a venture with two co-founders, randomly showing investors either the male or the female founder’s name alongside the characteristics of the venture. Encouragingly, their results show that experienced investors are equally likely to express interest in the venture whether it is presented with its male or its female founder. Among inexperienced investors (who never invested on the platform before), women actually show more interest in the venture when it is female-led, while men do not respond differently based on the founder’s gender. These results imply that equity crowdfunding could provide a remedy against the bias that female entrepreneurs face in more traditional equity investment contexts.

But what if there is bias not only against female inventors, but also against the type of inventions or products they generate?

But what if there is bias not only against female inventors, but also against the type of inventions or products they generate? While Sofia’s experiment held the characteristics of the venture constant and varied the gender of the founder, Rembrand Koning suggests that we also consider funders’ or evaluators’ responses to female-specific inventions. In his presentation during the IGL2019 Research Meeting, Rem emphasised the role of the inventors’ demographic background in shaping the type of problems they work on and the solutions they generate. For instance, biomedical research teams that include women are more likely to produce patents that focus on diseases or conditions that disproportionately affect women, and female-founded firms are more likely to sell products that are bought by female consumers. If the downstream players in the commercialisation process (entrepreneurs, VCs, lawyers from the technology transfer office, etc.) are mostly men, they may discount the potential value of inventions targeting women due to their unfamiliarity with the area (consider the funding struggles of a start-up that develops smart breast pumps, for example). Bringing more diversity to every step of the commercialisation process could encourage more women to present their ideas, resulting in a better allocation of talent – and more inventions focused on women, irrespective of the gender of the inventors.

–

At the IGL2019 Research Meeting we heard presentations from Sofia Bapna about her paper with Martin Ganco titled “Gender Gaps in Equity Crowdfunding: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment,” and from Rembrand Koning on a design stage trial titled “Finding Female Inventions and Inventors.”