Blog

IGL2017: My day of high growth, experimentation and failure

6 July 2017

On the second day of the IGL conference I had the pleasure to help facilitate four Policy and Practice Learning Lab (PPLL) workshops.

What works to support high growth entrepreneurship?

For the first workshop we set out to identify what works to support high growth entrepreneurship and business growth. The topic of high growth firms is something that Nesta has helped bring to prominence and which continues to gain traction (e.g. ScaleUp Institute in the UK).

As for many PPLL workshops, our approach to answering the question was to utilise the huge pool of expertise and knowledge amongst delegates in the room.

To get conversations started, Denis Medvedev outlined two opposing views of how useful it was for policy to focus on high growth.

My impression from a tour of the tables and a review of the notes, was that most placed themselves to the right of the scale. Recognising the benefits of targeting high growth potential but with most wanting to focus support on specific drivers such as innovation.

Next we sought examples of what worked. Sami Mahroum (INSEAD) kicked of the discussion drawing on his research to highlight 15 factors associated with the success of high growth businesses started in unlikely places. Examples and ideas provided by tables ranged from those that create a vibrant eco-system around high potential businesses (e.g. Scale-Up Demark); bring together private and public to provide equity finance (e.g. UK Enterprise Capital Funds) and support for new and small exporters (e.g. Australian Landing Pads).

The final section picked up the theme of experimentation. With Chris Haley (Nesta) asking tables to identify what new policy approaches should be explored and what areas would benefit from robust evaluation.

Public procurement was highlighted by many, coming up as both an area with untapped potential for supporting growth and where as a priority for identifying what really works. Support for innovation was another common topic, with questions raised about the best approach concerning tax credits, grants, loans, patent box… etc. From an IGL perspective is was gratifying to see many links to projects that IGL is already supporting through its trial grants programme or work with partners (e.g. the impact of incubators).

RCTs in innovation, entrepreneurship and economic growth:

Scope and application

Experimentation was the central theme of my second workshop. A rapid introduction to the use of Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) in innovation, entrepreneurship and business growth policy.

In this interactive session I was supporting my IGL colleagues, Triin Edovald and Teo Firpo, to take delegates through four questions that they will need to answer to run a successful trial:

- Can you learn something interesting?

- Is the programme suitable for running a trial?

- Is a trial technically feasible?

- Is there political will to run a trial?

During the session we utilised material developed for IGL’s Experimentation Toolkit, which was launched at the conference, and the Guide to RCTs that was published last year. We had a lot to cram into the 90 minutes but hopefully some attendees will be coming along to Boston next year to present their trials at the research meeting.

Reaching high impact businesses and entrepreneurs

For the third workshop we wanted to go back and test a premise from the first – that the success of innovation, entrepreneurship and business growth policy should be measured in terms of growth of individual businesses.

Xavier Cirera (World Bank) set out why policymakers may want to look beyond the growth of individual businesses. A key factor being externalities: a business’s growth can have negative externalities (e.g. it purely displaces the output of another) or positive (e.g. it develops local supply chains and prompts wider innovation). Julie Munk (Social Innovation Exchange) then presented examples to show how entrepreneurship policy can generate wider social benefits, such as drawing people into the labour market who may otherwise have been excluded or creating more environmentally sustainable solutions.

The table discussions generated a large number of suggestions for what policymakers should value.

Common themes being the quality of employment created (not just number) and the connections between the growing business and local communities and business networks. However, there was some concern that innovation, entrepreneurship and growth policy should not try and do too much.

Having identified what value policymakers should aim to create, we then asked tables to consider the implications for what types and businesses they should target and how to reach them, and then what support should be offered. To get this started Chris drew on the broad policy themes from Nesta’s Digital Entrepreneurship Ideas Bank whilst Julie gave examples used in Social Innovation. Again table discussions produced a diverse range of suggestions. Many on more traditional themes (e.g. R&D) whilst others perhaps novel – one group considering how to measure and reward the ‘social values’ of a business, for example their commitment to employees, ties to local community and development of their supply chains.

Useful failures: Learning from unsuccessful policies

For my final act at the PPLL, I joined Bas Leurs (Nesta), Grzegorz Drozd (European Commission) and Triin Edovald to run a workshop on failure.

This may not seem the ideal note on which to close the conference, but to help policymakers experiment new ideas and to run trials it is important that we can change perceptions about failure. Plus, we hoped the session we had designed would be fun as well as informative, luckily this proved to be the case.

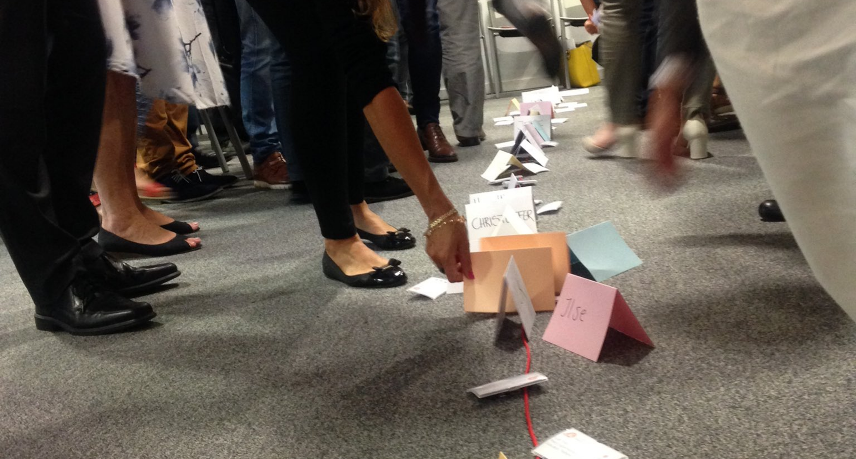

We started by asking delegates to reflect on how comfortable they and their organisation are with failure (The picture shows the line on which people placed themselves, and kudos to Bas for the ingenious way to collect name badges).

For many there were big differences between where they placed themselves and their organisation. Counter to my expectations, it was often individuals who, often through a personal drive to do things well, felt they were less tolerant of failure than their organisation. Our reflection on this was that to create room for failure we need to consider the psychological aspects and not just organisational.

We then proceeded to look at the causes of failure; whether some failures can be considered ‘good’ and others ‘bad’ and then how we can learn from the good and avoid the bad. Here we drew on many of the areas covered in a recent blog by Bas and his colleagues in particular Amy Richardson’s spectrum of reasons for failure. In summing up, Bas reflected that one element missing from the causes we had put forward, but common in many of the examples discussed, was “assumptions”. Assumptions are often the source of failure, taking something for granted, or considering something as being true for which you don’t have any evidence to warrant the claim. Innovation methods and tools, can help you identify knowledge gaps, assumptions or address other categories of cognitive and social biases. In another recent blog I also talked about how setting out the theory of change for a programme can help identify where trials may be of benefit by identifying key cause and effect assumptions that can be tested.

Many thanks to the all my co-facilitators at the workshops and to all the participants for their active and valuable contributions throughout the day.