Blog

The future is now: Citizen participation in R&I

27 November 2023

For four years, PRO-Ethics sought to test real-life applications of citizen participation in research and innovation organisations. The aim was to develop an ‘Ethics Framework & Guidelines’ that might enable ethical participation of citizens not just in research, but in strategy development, research topic definition and formulation, and evaluation processes of research activities themselves. This framework and guidelines now exist but the broader objective of opening research and innovation (R&I) to wider audiences, promoting inclusion and ultimately aligning the vast efforts of a sector where significant public money is invested with societal needs remains. The journey to achieving this has in many ways only just begun. However, there is evidence that this new way of thinking and doing is both an emerging and present reality across Europe and beyond.

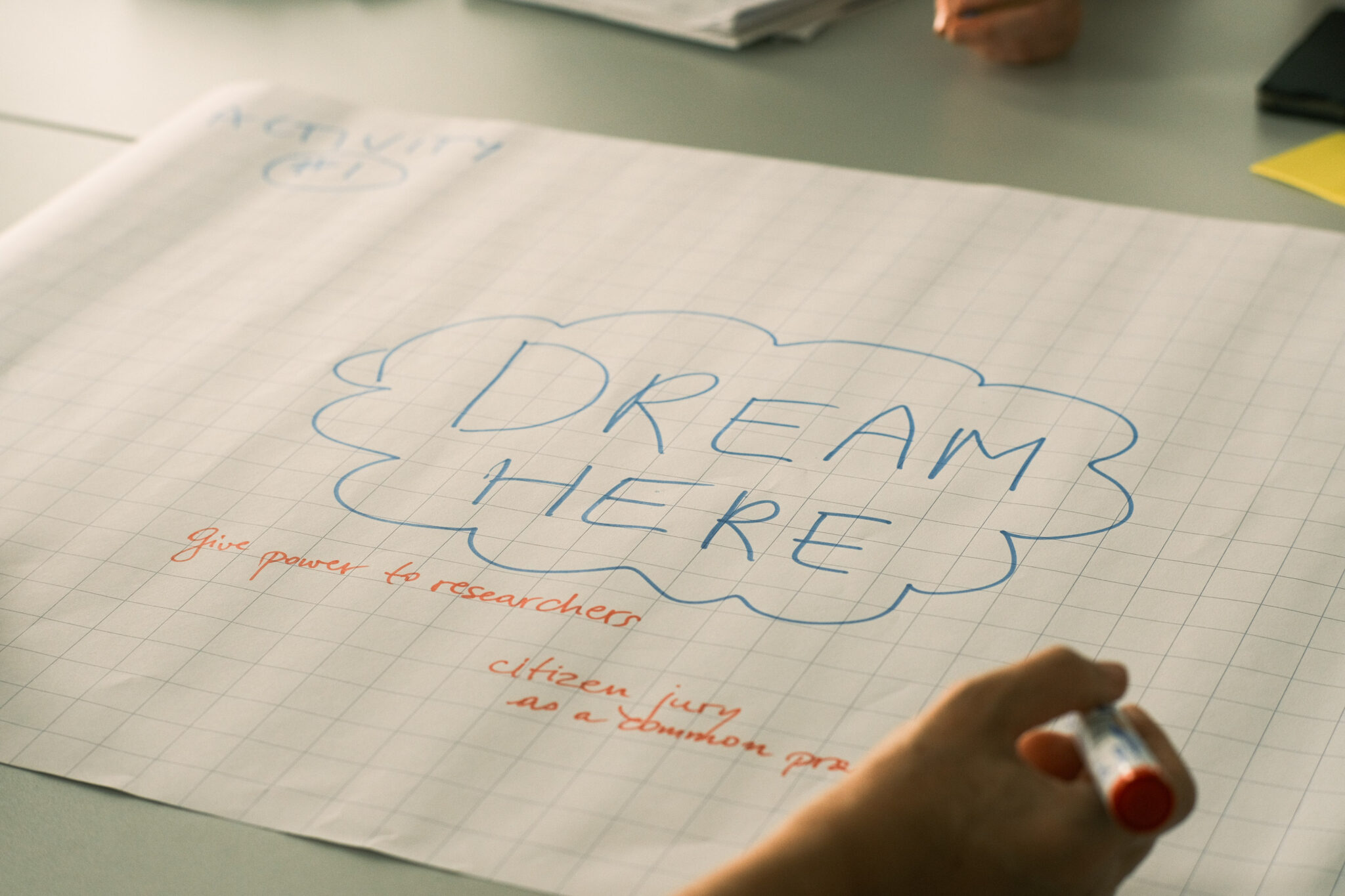

As part of the three-day conference ‘Connect. Collaborate. Create.’, held in Paris from 19-21 October 2023, the Innovation Growth Lab co-hosted a futures-oriented workshop aimed at identifying what decisions might need to be made today, in order to ensure the deepening of the participative pockets of R&I that exist today. This blog shares insights gathered from the workshop discussion with researchers, research funders and R&I practitioners present.

More room for play and experimentation

To begin the workshop, participants were asked to close their eyes and imagine a far future, ten years from the present date:

“Imagine…Science and innovation serves the needs of diverse communities through inclusive practices that bring citizens into the processes of research funding and research practising organisations. There is a balance of power between research and lived-experience experts, as well as consideration on non-human actors…”

“…Gone are the days when those with academic degrees had their knowledge valued more than others. Now, people of all backgrounds can be part of collectives that apply for funding, succeed in receiving it and feel at home in the world of academia. This is a collaborative future where multiple inputs are valued as we know how enriching this can be.”

“We will have reconfigured our understanding of what it means to work together in a productive manner. We cherish pluralistic approaches and welcome disagreement rather than trying to eliminate them, because we know they produce more robust outcomes.”

This imagined future is entangled with the idea of play and experimentation. For the participants in the room in Paris, room for play and experimentation was not only key for generating new ideas and supporting innovation at a community level, but also as a basis for participatory approaches to function. Play builds openness and responsiveness to needs, while experimentation creates the space and structure for new ideas to be tried, tested and to fail. PRO-Ethics and COESO pilots (21 individual cases if the projects were combined) are great examples of the many shapes participatory approaches can take. Yet, failure in R&I too often is discouraged by research funding structures that do not allow the space for exploration deemed to be too risky. The concept of ‘fail early, learn fast‘ is not new, but too many research practices remain entrenched. If iterative learning and managed failure were valued, encouraged and the norm we might see a greatly enriched R&I ecosystem. For participatory practices this would mean saying “yes” to trying diverse ideas, particularly those led by non-experts, and broadening our view of research practices recognised as ‘scientific’ (beyond academic publication and towards recognition of citizens who often lay the groundwork in regards to access, data collection and analysis). For example, participants noted that some citizen science projects have already started to ensure authorship is attributed to more than just academic researchers.

Patient research funding structures

The workshop IGL and partners delivered prompted participants to think about what might have to be true for the envisioned ten year future to be a success. This discussion centred a lot around the limitations of existing funding structures, that ask for transformative outcomes but are geared toward timelines that are not conducive to societal change. How can a community be impacted positively by a R&I project that has only been funded for one or two years, before the R&I topic shifts priorities elsewhere (and not on the basis of community needs)? Ethical citizen participation must therefore be adequately funded and real innovation at a societal level can only come from “patient” funding models. This term refers to funding given over a long period of time and with built in flexibility to meet research and community needs.

An example of this was given by a participant who highlighted the ComPASS funding programme in the United States. ComPASS provides long-term grants using a phased approach for planning and development, implementation and project assessment, dissemination and sustainability (funding the entire life-cycle of a project and giving security for community-led health research). The funding is said to be highly competitive because of the benefits to both research and societal outcomes – but the group was able to imagine what it might be like if more funding of this kind were available for participatory research in R&I; what impact might this have on entire systems?

Rethinking the role of the research funder in R&I ecosystems

Another useful provocation initiated by participants of the workshop was one that saw the role of the research funder as obsolete. What if R&I funding was allocated to anyone who applied to remove gatekeeping and fully adopt the notion that good ideas come from anywhere? What if research funding were allocated by lottery? What role would there be for the research funding organisations currently holding so much power on the kinds of research that gets funded (of course driven by their own obligations to Ministries and Government)? Our discussions didn’t quite come to a neat conclusion but I believe that the context that brought us together can.

Both PRO-Ethics and COESO projects give us a concrete preview of the future we might want to lean towards. Both were large-scale EU Horizon 2020 projects that brought together partners from across Europe to enable and incentivise the participation of citizens in research practices (PRO-Ethics focused on the role of research funding organisations, while COESO looks to bring the social sciences and humanities closer to the citizen science community). Both projects may have in many ways only scratched the surface, but they demonstrate a possible new role for research funders in enabling research projects rather than overseeing them. The future role for the research funder might not be to award funding but to support play and experimentation in a structured way, to support unusual collaborations (for example matching citizen-led research to researchers and resources), and to be a critical friend and support ethical applications of this new way of thinking and doing R&I.

What is true is that there is much to be hopeful about when imagining the future of research and innovation, when we consider it through the lens of citizen participation.The possibilities are many and potential lies relatively untapped. Anyone unconvinced by the benefits of citizen participation might very quickly find out that they have been left behind in the coming years because the future is very much here.

Photo by Emilia Rosario