Blog

Experimentation is more popular than you might think

24 January 2024

In IGL we’re firmly convinced that there are major benefits to experimentation in public policy, to find out what works and to make programmes work better before they are launched at scale. But it has never been clear how much our enthusiasm for experiments is shared among the wider public. We recently had the opportunity to look into this, and found that the public have a much better understanding of the need for experimentation than we’d realised.

In recent years we’ve seen uproar in the media about technology companies carrying out experiments. In our work in IGL, we sometimes hear concerns that randomly selecting participants for a programme will be perceived as unfair. For example, this was one of the most commonly-cited barriers to the use of RCTs that arose in an IGL survey of researchers and practitioners (though it’s notable that this concern was restricted to those who had not been involved in carrying out an RCT). And the word ‘experiment’ itself can have negative connotations due to abuses in the past.

Several teams of researchers have recently started looking into this question. A team working in a health care setting in the US found that in many situations members of the public prefer direct implementation of an untested intervention to carrying out a randomised experiment to test how well that intervention works. But others have argued that these results are not generally true. Another paper looked at the acceptability of experimentation on the part of corporations, and found that experiments were usually viewed as no worse than the least-preferred of the two options being tested. And a recent study in the Netherlands found that survey respondents in the Netherlands mostly had positive attitudes to experimentation in public policy.

IGL (working together with Nesta’s Centre for Collective Intelligence Design) recently carried out a survey of the general public in six EU countries, as part of our work with the European Commission to promote experimentation in research and innovation policy and to promote citizens’ engagement in the EU Missions. We used this as an opportunity to test attitudes to experimentation across a large sample in countries ranging from Romania to Ireland.

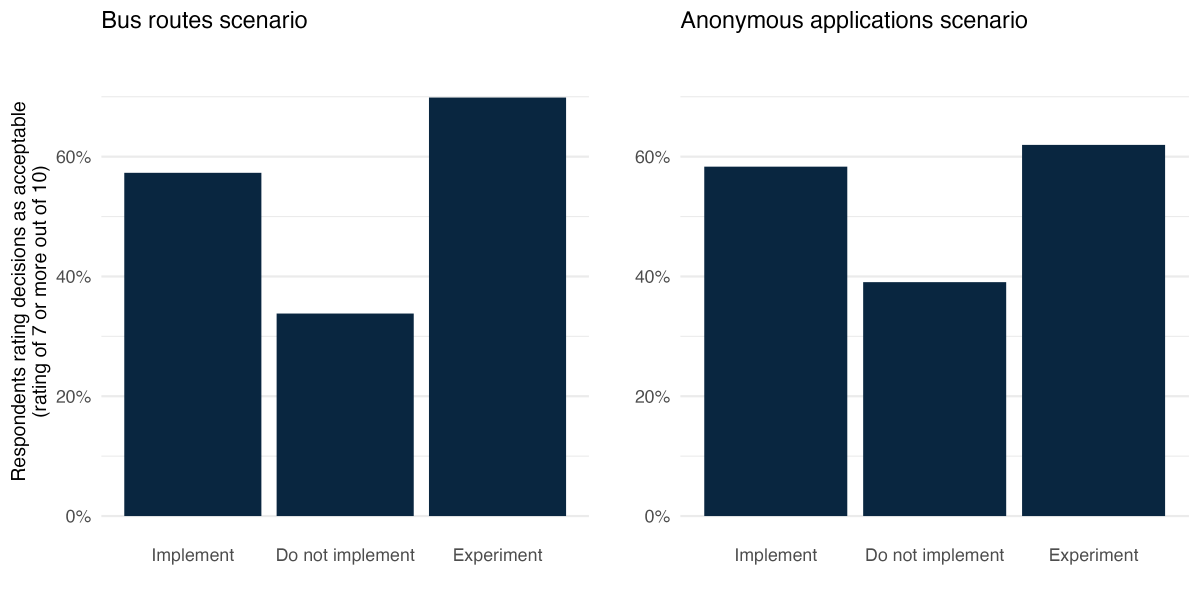

In our survey we directly replicated one of the questions from the recent Dutch study (about a municipal authority considering introducing an anonymous application process for job vacancies) and also added a scenario of our own, about improving the local bus network. In each scenario, we asked respondents to imagine that their municipality had three choices: they could either (a) implement the new approach, (b) not implement it, or (c) carry out an experiment, testing the new approach in a structured way (implementing it with some job postings or some bus routes but not others) before deciding whether or not to implement.

We found that survey respondents were very accepting of the idea of experimentation. As in the Dutch study, we found that clear majorities of respondents (64% in the public transport scenario and 58% in the anonymous applications scenario) viewed experimentation as the best or the joint-best of the three options. Only 9% saw experimentation as worse than either of the other two options. This backs up the finding from the private-sector context that only a small minority see experiments as worse than either of the two options being experimented with.

Figure 1: Acceptability of experimentation

We also tested whether people had particular misgivings about the word ‘experiment’ or about the idea of random selection. When presenting the experimentation option in the survey, we explicitly described this as an ‘experiment’ to some respondents, but simply as a ‘test’ to others. We also varied whether people were told that the proposed experiment would involve randomly selecting the job postings or the bus routes to be affected. To our surprise, we found that using the words ‘experiment’ or ‘random selection’ made no difference at all to perceptions of the acceptability of experimentation. This is backed up by another recent paper, which found that the word ‘experiment’ did not make a difference to the overall positive attitudes to local-level policy experimentation in Germany.

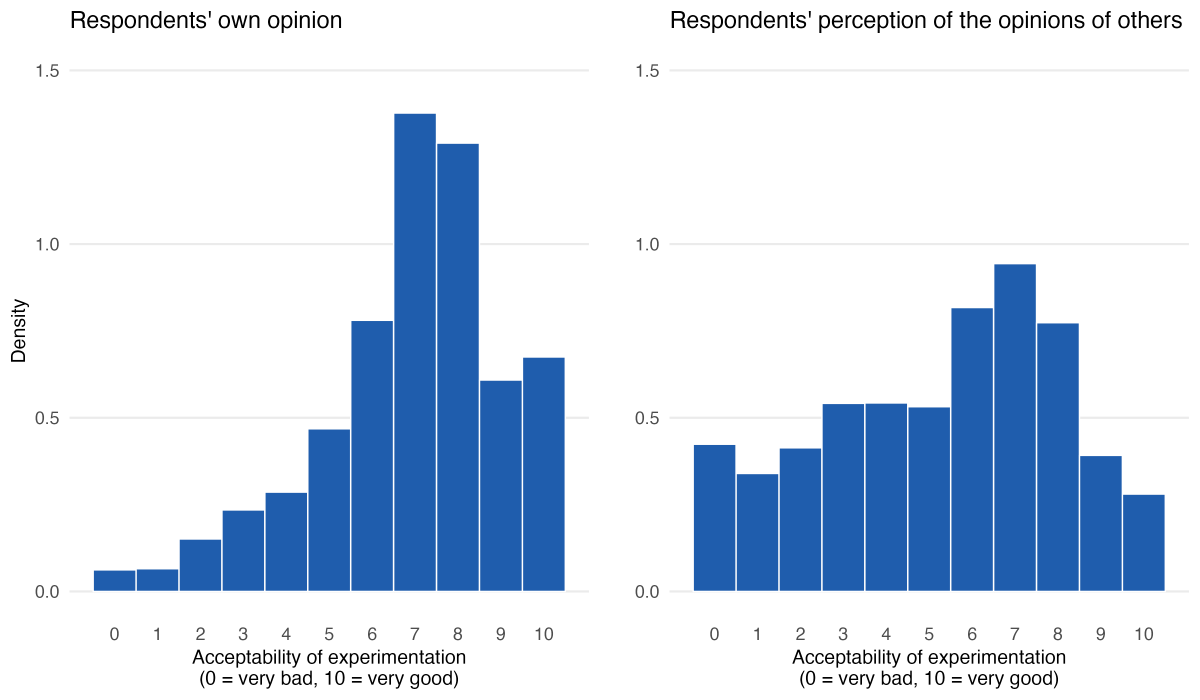

Another interesting finding from our survey – which again is consistent with the Dutch study – is that many of the survey respondents thought that other people would see experimentation less positively than they do themselves. We don’t know whether this is because our survey respondents (simply by virtue of being willing to participate in an online survey) are atypical of the broader population, or whether people in general are overly pessimistic about others’ opinions.

Figure 2: Perceptions of the acceptability of experimentation at the municipal level

In any case, our findings are positive in that the public seem to have some understanding of the benefits of experimentation and are receptive to its use. We have long believed in the power of experiments to learn about how to make public policy more effective, so it is good news that the ultimate beneficiaries are also open to this idea.

This blog is a summary of the findings developed in “Peter BAECK, Rob FULLER, Christopher EDGAR, Andrea BLASCO, Edoardo TRIMARCHI, James PHIPPS (2023) “Citizens’ awareness of EU missions and opportunities for citizen engagement: Results from a multi country survey”. European Commission, R&I Policy Series”