Blog

Building Collective Capacity For Experimentation

Improving Strategy and Policy by Investing in the Infrastructure for Collective Experimentation

17 April 2025

This blog has been cross-posted from Sharique Hasan’s personal Substack blog.

Sharique Hasan: This post is a bit more personal than usual. It’s about our journey at CFXS and IGL to build capacity for field experimental research that addresses pressing challenges in strategy, innovation, and entrepreneurship. The larger collective goal is to drive better business and policy decisions that create prosperity.

Starting Small and Hitting Walls

In 2007, I collaborated with a friend and classmate from Carnegie Mellon, Surendrakumar Bagde, on a field experiment in India. We were studying knowledge spillovers and network formation at an Indian college. It was a bit serendipitous that we got to run the experiment (ask me about it sometime). I didn’t know many people doing field experiments then1—it wasn’t common in the graduate program I was part of. And when I started my first job, field experiments were not on the radar in organization theory or strategy.

For some reason, my early studies were accepted fairly easily (one in the American Sociological Review and the other in Management Science). But when I shifted toward more traditional organizational/strategy topics like entrepreneurship, publishing became a real beast. My work didn’t seem to fit and kept getting rejected. I could wax philosophical about why the papers were rejected. Looking back, I’m sure it was a mix of things—imperfect research designs, skeptical reviewers, and my own blind spots around what excited people in that part of the field.

Anyway, there was a gap of nearly four years between when the experiments with Surendra were published (in 2015) and when my next set of experimental studies finally came out (in 2019). That stretch was rough. Can’t lie. Constant rejection wears on you. You begin to wonder whether you’re cut out for this business. But great guidance from thoughtful editors and support from my colleagues at Duke really made the difference.

Finding Each Other

By 2019, I had started meeting more researchers who also seemed to be banging their heads against the wall trying to get their experimental work published. I kept hearing the same kinds of stories—reviewers who didn’t understand why randomized experiments allow for causal inference (“they kept asking for more control variables!”), struggles with implementation and reviewer skepticism about whether we learned anything from the experiment.

At the time, I was also an Associate Editor at Management Science, so I saw firsthand how difficult it was to find reviewers who understood both experiments and the substantive topic well enough to guide a paper toward successful publication. It was also clear that experimental research in strategy was still in its early stages, and without support for people in our field who were experimenting with experiments, the incentives might soon shift away from doing them at all.

It was clear that it was a “system” problem rather than just the failings of individual researchers or bad reviewers. We hadn’t yet built the collective capacity to experiment in ways that would help us learn as much as we could.

That is, individual researchers were struggling, but our field also lacked a system that made field experiments viable: incentives, reviewers, resources, training, and developmental publication venues.

Something needed to be built.

Collective Experimentation

It is worth stepping back at this point and asking: Why should we focus on improving collective experimentation in the field rather than having people just read Gerber & Green?

While there are clearly individual incentives to get one’s experiment published, I think the collective goal of our efforts is something entirely different. It is to drive better decision-making—at key leverage points in business strategy, entrepreneurship, and public policy— through rigorous evidence so that our societies are collectively more prosperous. It is both about how the ideas are tested, but also what ideas are tested.

In addition to my experimental research, I’ve been working with colleagues to think about the “collective” part of experimentation more recently.

Experiments versus Experimentation

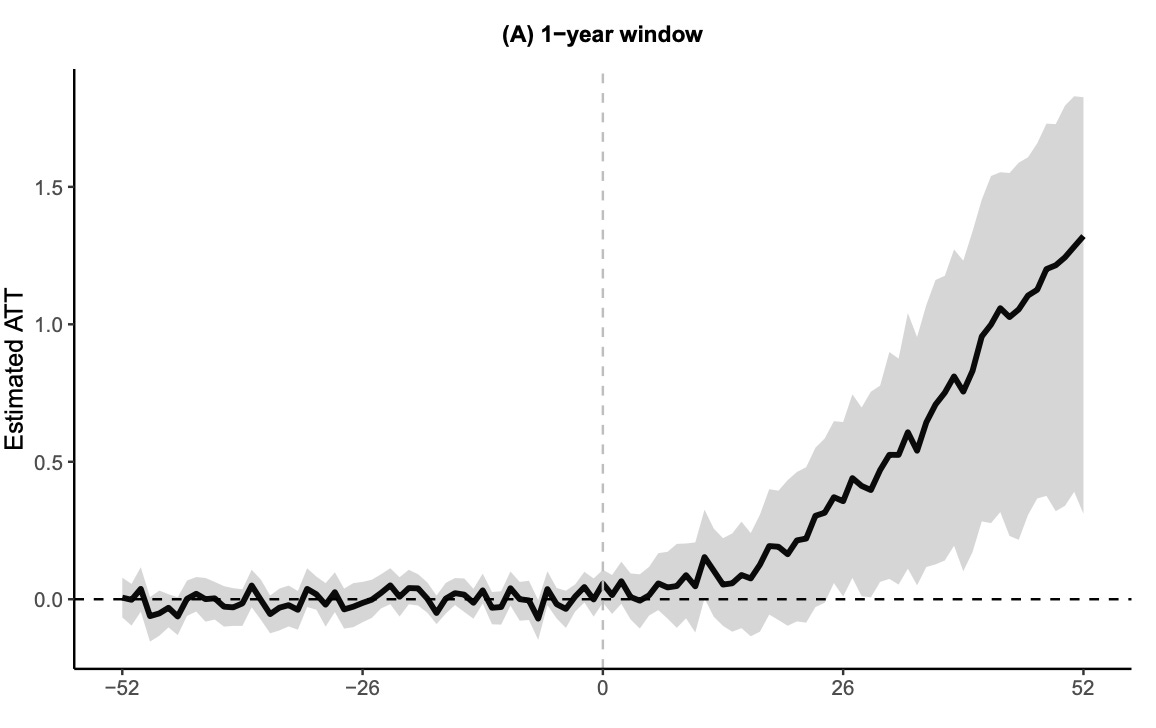

The first study that got me seriously thinking about collective experimentation was with Rem Koning and Ronnie Chatterji (Experimentation and Startup Performance). We tracked thousands of high-growth startups in the paper and found those who adopted formal experimentation (e.g., A/B testing) [Note: An experiment is a one-off empirical exercise. Experimentation is the collective ability of the organization to run many experiments to drive strategy towards a particular vision.] Individual experiments become vehicles for directional change when embedded into a collective effort and strategic process.

But the key word here is collective. A/B testing only made a difference when it was integrated into how firms made strategic choices—when it helped the organization explore many bold ideas, not just test one-off theories. If we want field experiments in innovation and strategy to matter, we need to treat experiments not just as evaluations of interventions but as explorations of what is possible a la March (1991). That is: They shape what people are willing to try next. And if we can surface the right ideas, then we can shift the direction of collective learning.

Managing Risk versus Progress

In a separate collaboration with Todd Hall (Organizational Decision Making and The Returns to Experimentation), we modeled what happens inside organizations when experimentation meets decision-making. Organizations that either centralize too much or decentralize too loosely lose the benefits of collective experimentation. Either they slow down innovation by over-controlling which experiments get implemented, or they allow too much noise by letting every random finding get committed into policy.

The sweet spot is a structure that decentralizes the generation and running of experiments—but maintains some consistency in what counts as sufficient evidence to scale. This matters a lot when we consider how collective experimentation’s value scales. Communities should provide consistent thresholds and norms about recognizing when experimental evidence counts as credible.

Driving Diversity In Hypotheses, Not Just Maximizing Significance

In more recent work with Ashish Arora and William Miles (If You Had One Shot: Scale and Herding in Innovation Experiments, NBER Working Paper 33682), we explored how the distribution of experiments across firms affects experimental diversity (e.g., which hypotheses and approaches are tried) and eventually, which problems get solved. Our central finding was counterintuitive: when many firms each run just one-off experiments, they tend to herd. Everyone bets on the same “most promising” idea. What would you do if you had one shot?

But this behavior creates systemic risk. If the most popular approach turns out to be a dead end, the entire market of experiments fails together.

Organizations that can run multiple experiments face a different calculus. They have an incentive to diversify because they only need one success to generate value. Spreading their bets across different approaches lowers the risk of total failure. By internalizing the cost of correlated failure, multi-experiment firms naturally hedge.

This finding, I think, has implications for how we structure research communities. If we want to make progress on hard, high-uncertainty problems, we need mechanisms that encourage approach-level diversity. That might mean funding multiple early-stage pilots instead of doubling down on the most promising idea. It might mean supporting researchers over the long term who can try multiple paths. It means building a community that values novelty and risk.

Yes, rigor matters, but so does trying new and challenging things.

Thanks for reading Superadditive: Deep dives into innovation and organization! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Building Capacity

Let’s start building.

Meeting others who had gone through similar struggles was incredibly eye-opening. Solamen miseris socios habuisse doloris: it is a comfort to the unfortunate to have had companions in woe.

I guess a community begins when isolated people realize they’re not alone. Karim Lakhani at Harvard Business School generously covered food through his LISH lab, and Vish Krishnan at UC San Diego was incredibly supportive. Duke I&E provided the space, and my personal research budget covered breakfast, a Costco run for drinks and snacks, and a lot of elbow grease. We also had a fantastic project manager, Camille, who made the logistics a breeze.

We organized the first workshop—Workshop on Field Experiments in Strategy, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship (long name, we would change it later)—at Duke University in January 2020. We invited researchers from around the world who we knew were doing experiments. We were hoping for 30 or 40 attendees. We got 60 attendees over the two days. Not bad for a new conference built around a method that wasn’t widely used in the field.

The people who came included both early-career and more senior researchers (many still participate in CFXS today—thanks, Tom and Jana!). That first year, we also had a phenomenal panel with my Duke colleague Wes Cohen, Alfonso Gambardella from Bocconi, and Albert Bravo-Biosca, a friend of Karim’s from an organization I hadn’t heard of before—IGL.

Then COVID hit. The world shut down.

Who knew whether we could ever run the workshop ever again?

Fortunately, two young scholars, Rem Koning at Harvard Business School and Hyunjin Kim at INSEAD—both brilliant, fun, creative, and incredibly hard-working—stepped in to keep the conference going. We had initially thought about organizing the 2021 conference in person, but the COVID lockdowns and travel restrictions made that unworkable. Moving it online turned out to be a revelation.

In my view, the second conference (yes, the online one) was at least two to three times better than the first. Over 80 people attended, from all around the world. The conversations were incredible. You could feel a real hunger—not just for the ideas, but for the kind of community we were building. We were intentional about setting the culture from the start.

Our community would be intellectual, but fun. Rigorous, but kind. Open to diverse ideas, but with a strong emphasis on integrative discussion.

Most of our discussants were senior scholars, and they were asked to read and synthesize two, sometimes three, papers at a higher level of abstraction, drawing on their experience to help connect ideas across presentations. That takes a lot of work, and you could tell the discussants were really thinking hard about the papers.

After that conference, Albert Bravo-Biosca asked if we’d be interested in co-hosting the next one in London with the Innovation Growth Lab.

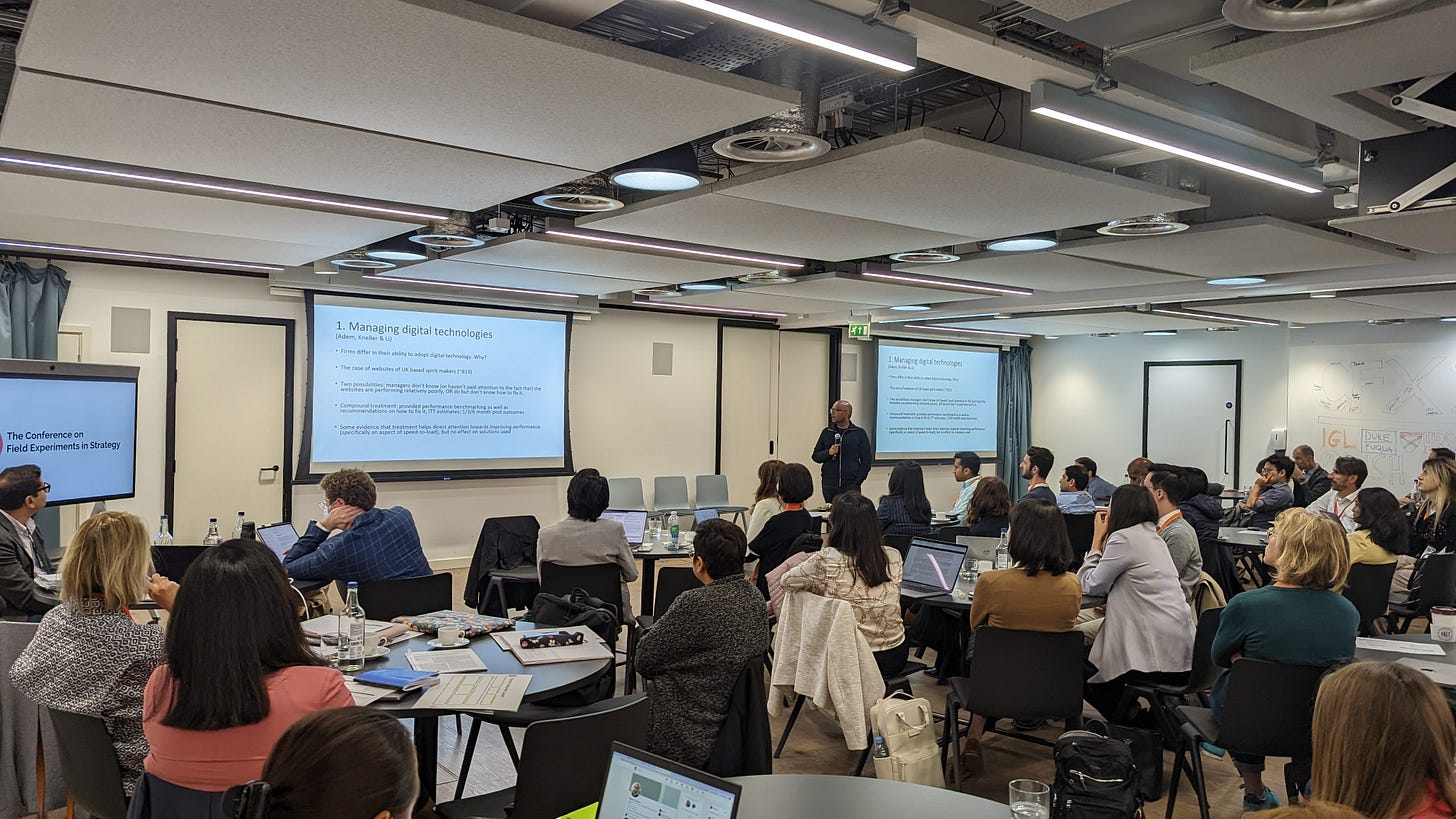

The IGL team—Albert, Yan Yan, and Edoardo—put together an incredible venue at the NESTA offices. That year, at CFXS3, we introduced a few new features to the conference. One was the idea pitch sessions—no full experiments, just early-stage concepts. We realized that a key problem we needed to solve for was getting feedback to people before they ran their experiment. This feedback could help save time, money, and headaches. Edoardo also brought in Slido, allowing participants to give live feedback in real-time. It was crowdsourced feedback in five minutes, simple, fast, and incredibly useful. We wanted to move beyond giving feedback to experiments that had already been run but, rather, to help researchers improve the experiments still incubating.

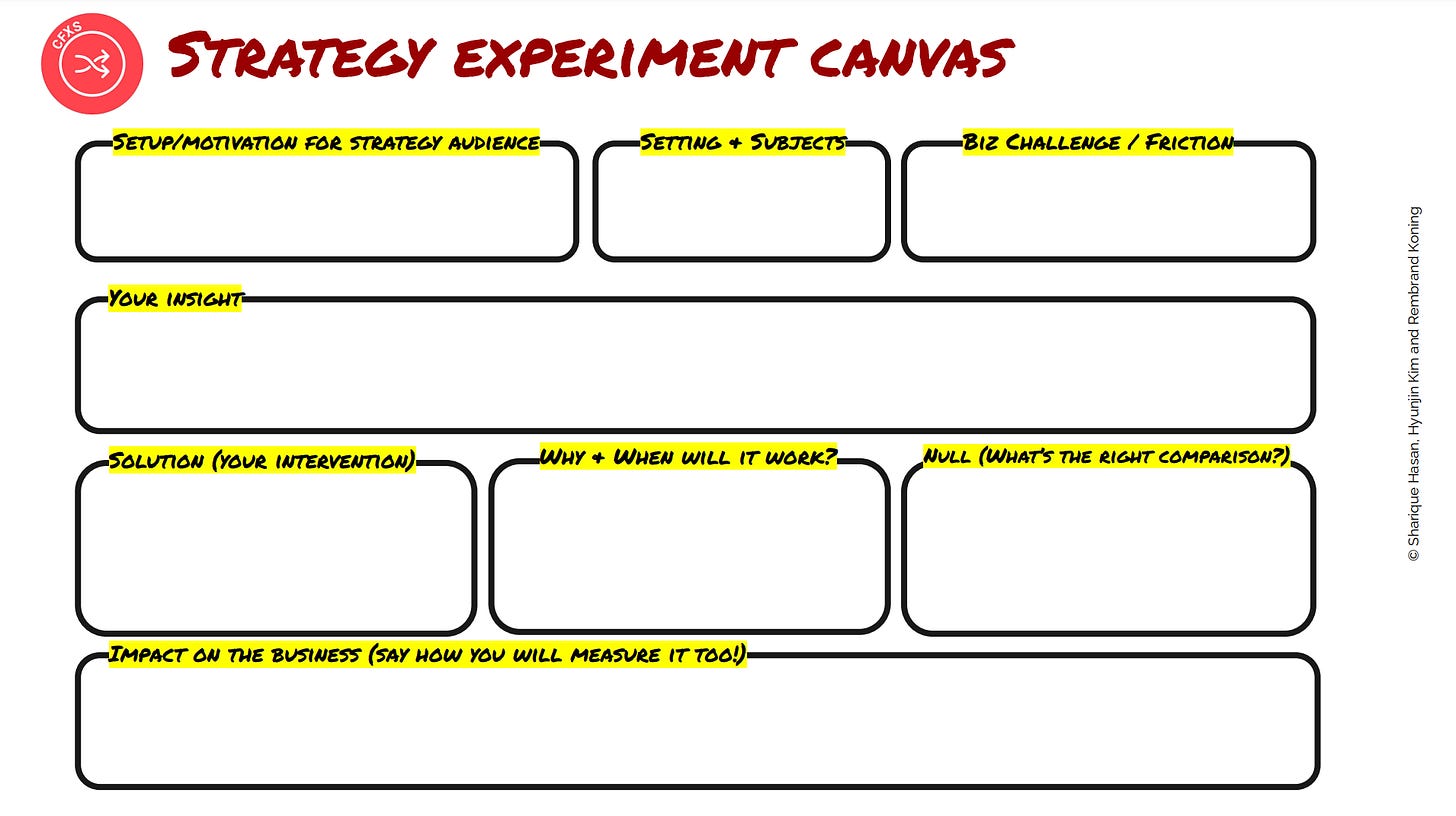

We also launched a PhD workshop on the morning of the first day, with nearly 30 students in attendance. Most PhD programs in strategy still don’t teach experimental design. If we wanted better collective experimentation, we would need to start with PhD students. To guide those sessions, we realized we needed a shared language for designing strategy experiments. Taking inspiration from the Stanford d.school, we created our own Strategy Experiment Canvas.

CFXS4 was held Cambridge, MA with much the same format as CFXS3. But this time, we had over 100 people attend over the two days of the conference. Clearly, we had hit on something.

If you asked attendees whether CFXS was a “methods” conference, the answer was a resounding no. A field experiment was not just a technique; it was a way of thinking about the world: How do we find leverage points to help change the world in a positive direction?

Scaling Impact with Philanthropic Support

Building on the success of CFXS4, we decided to formally connect IGL and CFXS’s efforts in organizing experimental capacity building. We applied for and were awarded a Sloan Foundation grant last year to help build out this community even further. The grant would support a range of initiatives, including:

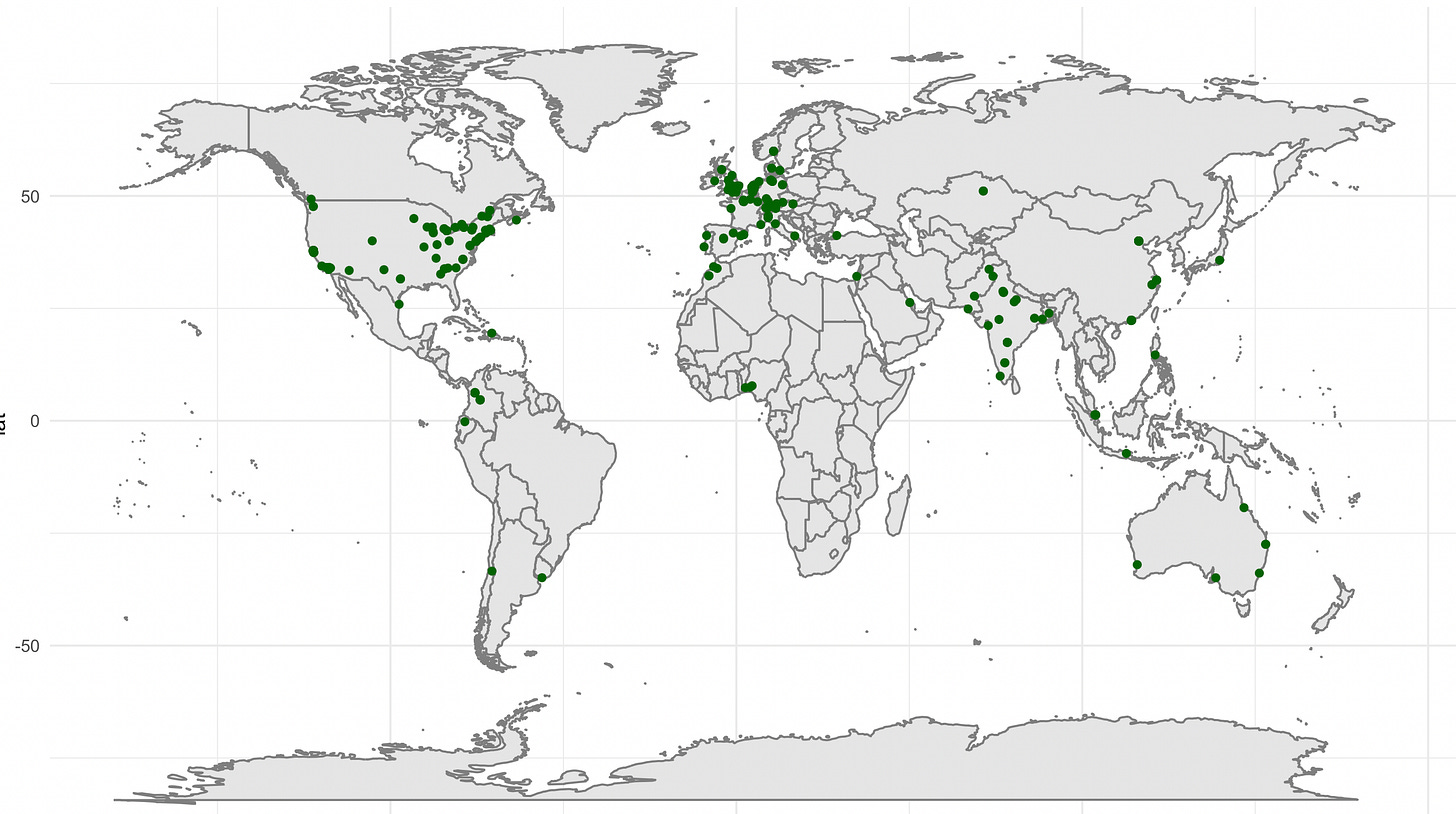

- Build a vibrant and diverse research community by integrating the IGL and CFXS networks and expanding access to training, funding, and collaboration opportunities. We also provide travel support for PhD students attending programs that can not support travel to conferences. [join the research network] [check out research network members]

- Foster learning, feedback, and knowledge sharing through conferences (CFXS), webinars, PhD workshops, masterclasses, and mentorship programs.

- Provide seed funding for early-stage experimental ideas that lack traditional sources of support. [learn about our seed funds]

- Reward and recognize outstanding research with annual prize awards to highlight impactful and innovative experimental work. [awards to be announced soon]

- Create and disseminate research resources—such as design toolkits, data collection templates, outcome measurement instruments, and matchmaking services with implementing partners. [coming soon!]

And more long-term goals, including:

- Strengthen the link between research and practice by enabling partnerships with government agencies and organizations interested in experimentation.

- Advance evidence-based policy and business practices by increasing experimental research quality, quantity, and visibility in the U.S. and globally.

With Sloan Foundation support, CFXS5 was held at INSEAD in Fontainebleau, France, in December 2024.2 In 2024, our team got its newest member, Anna Giulia Ponchia. Check out her write-up about CFXS5.

Just last week, we wrapped up a six-week master class on field experiments. The speakers included Liz Lyons (UC San Diego), Jana Gallus (UCLA), Chiara Spina (INSEAD), Thomas Astebro (HEC Paris), George Ward (Oxford), Nicholas Otis (Berkeley), Jackie Lane (Harvard), and Florian Englmaier (LMU Munich). The topics the masterclasses covered ranged from experimental failure to using GenAI in experiments:

- Setting Up an RCT at Scale – Ensuring robustness in RCTs, including strategies for negotiation, navigating set-up challenges, and learning from near-failure experiences.

- The Importance of Power in Experiments – Addressing low-powered studies and strategies to increase sample size, such as within-subject design approaches.

- Team Science & Organizational Economics– Exploring collaborative research within organisations and teams

- Scientific Approach – Applying scientific methodologies to entrepreneurship.

- AI & Experiments – Running online experiments using AI with entrepreneurs in developed and developing economies.

- What Happens When an Experiment is Over – Insights into refining experiments through pre- and post-mortem analysis.

- How to make your experiments more rigorous – Getting feedback and knowing what to focus on.

If you want access to the videos, please sign up here.

Nearly 400 people from around the world registered for the masterclass. Around 270 participated in the asynchronous sessions; an average of 80 joined the live classes across the six sessions. I’m lucky to get five students in a PhD class; 80 is a treat.

If there’s one thing we’ve learned in slowly building CFXS, it’s that the capacity to experiment—and to learn—depends on more than good ideas or individual effort. It requires building shared infrastructure and public goods: tools, training, funding, and feedback loops that make high-quality field experiments possible at scale.

The support from the Sloan Foundation and collaboration with IGL have made it possible for us to scale our efforts in a way we could never have imagined. But most of all—what keeps the flywheel going is the community of people who have continued to share and engage year after year. Thank you!

With PhD education under pressure and institutional support becoming less certain, we need to think more carefully about how we continue to develop the next generation of scholars. If we want strategy and policy—and social science research in general—to be more evidence-based, we must collectively invest in institutions that make that kind of learning possible. This is a first-order mission that should drive our efforts.

We’re excited about where the IGL/CFSX collaboration will take us next. San Francisco, actually. 🙂

Keep an eye out for the announcement for CFXS6.

See you in San Francisco.