IGL’s Global Conference, held on 25 May 2016 in London, was a great opportunity to discuss the role of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in innovation, entrepreneurship and growth policy.

RCTs tend to offer the best means to determine whether a policy or a programme is achieving its aims and desired impact. Unfortunately, RCTs have been rare in innovation, entrepreneurship and growth policy. Even though we could benefit from more RCTs in this domain, it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t consider other ways to improve our ability to learn and do things in a better way to achieve the desired results.

To explore these issues further, we ran a session ‘Learning from policy experimentation: Some alternatives beyond RCTs’ at the conference. The session brought together experts who were willing to share their insights on when and when not to use trials – and importantly, consider alternative approaches that could be used in policy experimentation:

- Ken Warwick, Economic Consultant, Warwick Economics; Member of the UK Regulatory Policy Committee; Former Director of Economics, Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) (UK)

- Lucy Kimbell, Director, Innovation Insights Hub, University of the Arts London (UK)

What new developments have there been in industrial policy and evaluation?

Ken Warwick spoke first, drawing on his long experience in industrial policy and evaluation. He set out that overall, there has been a shift in industrial policy from firm-based programmes towards an emphasis on systems, networks, coordination; greater alignment of policy planning with needs of industry; and technologies or broadly defined sectors rather than single firms. Parallel to that shift in industrial policy there have been changes in the evaluation practice. Namely, we’ve witnessed a greater use of RCTs and experimental methods; piloting and evaluation; better microdata and econometric methods and the emergence of developmental evaluation.

The latter differs from traditional evaluation methods in that the focus is on providing feedback, generating learning, supporting direction or affirming new direction. Developmental evaluation positions itself as an internal, team function integrated into policy development with a focus on capturing system dynamics, interdependencies and emergent interconnections as opposed to traditional evaluation where the design is based on linear cause-and-effect logic models. In terms of learning, developmental evaluation aims to produce context-specific understanding that informs further policy development. In other words, the aim is not to produce findings generalisable across time and space.

Ken also raised a concept of choosing your evaluation techniques depending on whether the intervention is simple (a single instrument), complicated (a package of related instruments), complex (where uncertainty is high and the effect of interventions may be non-standard and highly context-dependent), or complex and complicated (typical of new industrial policy where a package of measures is being applied in an environment of uncertainty).

According to Ken, simple single measures with well-understood outcomes would benefit from RCTs the most. However, it is important to avoid an evaluation bias towards simple problems. Just because they may be hard to evaluate, ‘softer’ interventions may be just as important for growth but harder to evaluate. Complicated interventions would benefit from applying single measure techniques to components where possible while taking account of interactions and multiple treatments and influences. Complex interventions would benefit from iterative approaches to evaluation using a range of qualitative methods to test/learn/adapt as quantitative methods may be difficult to apply. However, when it comes to complicated and complex interventions, counterfactuals (i.e. comparing the observed results to those you would expect if the intervention had not been implemented) may not be possible. Instead, one might benefit from applying single measure techniques to components, take account of interactions and systemic effects, and use qualitative measures and more informal methods of learning by doing. In all, evaluation of complicated and complex interventions requires an iterative, eclectic approach.

What about design approaches to early stage policy-making?

Ken Warwick was followed by Lucy Kimbell, who specialises in design approaches (sometimes called ‘design thinking’) and who discussed the use of them in early stage policymaking. Lucy is affiliated with the Policy Lab UK – an organisation that is a proving ground for new policy tools and techniques. The Policy Lab was created to help re-invigorate policymaking, making it more user-centred, iterative and open to future digital practice. The Lab works with policy teams to help them apply new approaches in live projects.

Lucy pointed out that to solve cross-cutting problems, there are three components that need to be considered:

- Politics: Understanding and managing the political context

- Evidence: Developing and using a sound evidence base

- Delivery: Planning from the outset how the policy will be delivered

The design question is: How can we bring it all together?

Drawing on her report ‘Applying design approaches to policy making: Discovering Policy Lab’, Lucy introduced the idea of an abductive approach that is used by the Policy Lab, where things are linked together in new ways. According to Lucy, the process of abduction ‘creates tentative explanations to make sense of observations for which there is no appropriate explanation or a rule in the existing store of knowledge’. It differs from deduction since we can’t take a general rule and see what follows in particular cases. Nor can we say it has strong validity because of the observations we made, as with induction. But with abductive reasoning, what we do get is a new insight or concept that we can explore further with the other two logics. While RCTs align nicely with the deductive approach, the abductive approach makes use of exploratory prototyping.

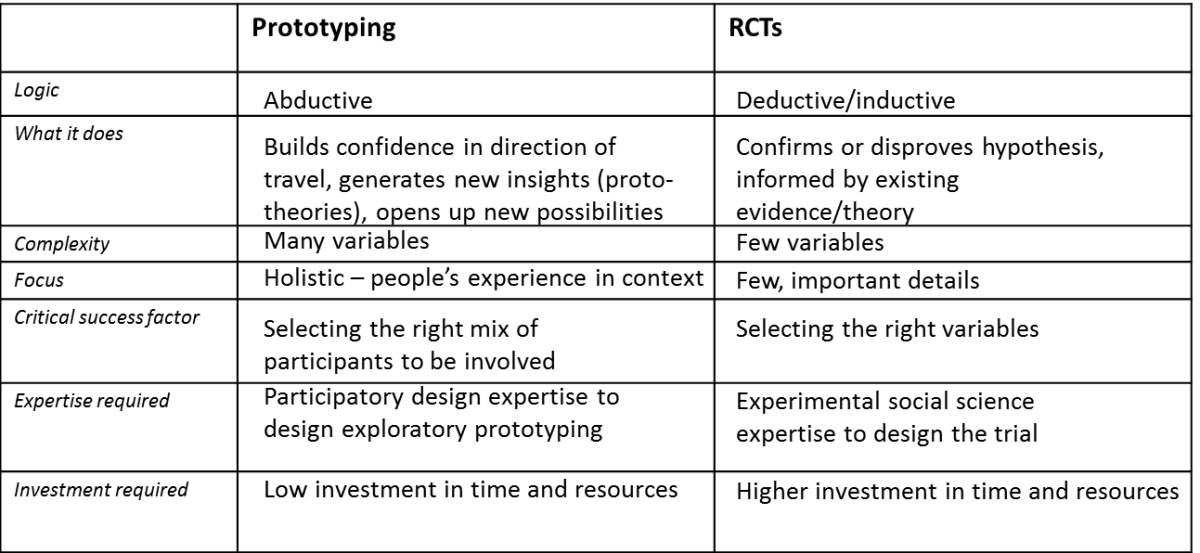

What are the differences between prototyping and RCTs?

Lucy Kimbell set out the key differences between prototyping and RCTs across a number of aspects ranging from logic to investment required. These are shown in the table below.

Source: Lucy Kimbell's Twitter.

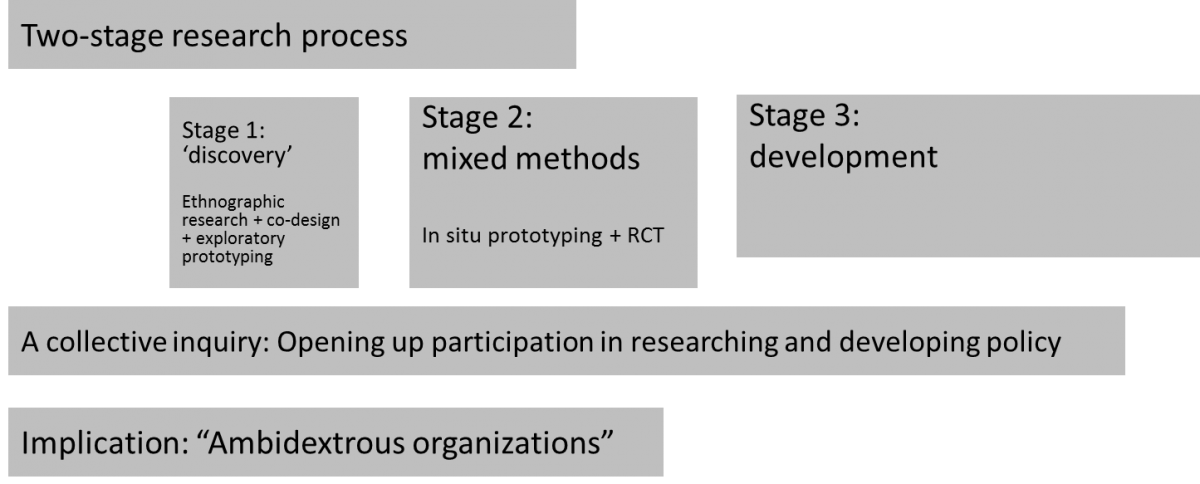

Lucy also discussed how prototyping can intersect with RCTs/other methods for early policy evaluation.

Source: Lucy Kimbell's Twitter.

In all, the key characteristics of the approach Lucy introduced are that it is based in:

- Abductive discovery, through which insights, guesses, framings and concepts emerge (e.g. ethnographic research, co-design, prototyping in the fuzzy front end of policy-making).

- Collective inquiry – through which problems and solutions co-evolve, which is participatory, and through which constituents of an issue are identified and recognised, and solutions are tested (e.g. prototyping).

- Recombining experiences, resources and policies – the constituents of an issue – into new (temporary) configurations.

Concluding remarks

When it comes to policy experimentation, a range of methods can be beneficial depending on the stage of policy design, questions that policy-makers are interested in asking, and the feasibility of applying different methods. The key is to be open to a range of methods and think about strategies for dealing with complexity rather than zooming in on solutions that are easy to define and evaluate.

Policy-making is a cyclical process with a number of stages ranging from agenda setting and policy formulation to evaluation, and policy maintenance, succession or termination. The emphasis on the cycle shows us how fluid policy-making really is. However, it is still possible to consider policy experiments at various stages of policy-making and make use of a variety of methods including prototyping instead of waiting until the end of the process, so an ex post evaluation can be carried out.

Please note that one of the panellists - Patricia Rogers, Professor in Public Sector Evaluation, RMIT University; Project Director, BetterEvaluation (Australia) – was not able to join the session due to technical difficulties encountered.